The Left in Diaspora

Who are the voters of the left today? And why are they so few in the last two decades?

“I have never been shy to say out loud that I love my wife. Same as I’ve never shied away from saying that I am a leftist,” says Henryk Milczarski from Radom, born in ‘59, ever a left-wing voter.

In the early 2000s, Henryk and his wife Bożena, Catholics with ties to the Jesuits of Radom, organized charity picnics and community meetings. Thousands of people attended: children, families, politicians, businesspeople, social activists. All the attractions at the picnics were free.

But when a new parish priest arrived, Henryk was ousted as organizer. Cause? He was a leftist. “One of the priests told me directly that if he knew who I was, he would never have shaken my hand. Another turned his back on me and my family. That hurt the most. Only the City Social Welfare Centre director had the courage to stand up for us,” says Milczarski. “A year later, the participants of the picnics had to pay for everything.”

Maciej Niedźwiedź from Warsaw, a voter of the Razem Party, three decades younger than Milczarski, goes to tenants’ protests and eviction blockades just as often as he goes to church. As a volunteer at Kancelaria Sprawiedliwości Społecznej [Social Justice Office, an initiative offering legal aid – transl. note], he helps people who cannot afford rent. He has probably seen it all. Landlords who throw single mothers out on the street without batting an eye. Apartment “cleaners”, who, in order to get rid of tenants, take the toilet out of their bathroom. “For the first few months working there, I had nightmares,” says Maciej. “I would wake up at night terrified, thinking ‘I’m about to be evicted.’”

Kama Siwek, same age as Maciej, is a climate activist. When we talk, the election campaign is underway. Climate organizations are jointly preparing to send “yellow cards” to politicians of the ruling coalition. On the cards they have written unfulfilled promises, such as the one to end deforestation, or to ensure climate neutrality. Under the posts detailing the action, Kama reads comments saying there are more important things than “some forest or another”. “But what is more important than the fact that we are seeing yet another year of drought in Poland? Is there really anything more important than what we eat, what we drink, and what kind of air we breathe?” Kama asks. She regrets that she cannot vote for the Greens anymore. In her opinion, the party has become too merged with the Civic Coalition and its voice is not heard in the public debate.

Left-wing voters do not speak with one voice and are not a monolith. So, who are they? What does leftism mean to them? What are their lives like in a country that has been ruled by the right for two decades?

Secularized and disappointed

A quarter of a century ago, the left held full power in Poland. In 2000, Aleksander Kwaśniewski began his second term in the presidential palace. A year later, the coalition of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) and the Labour Union (UP) won over 41 percent of the vote in the parliamentary election. For the first time in the history of the Third Republic of Poland, the Social Democrats controlled all of the most important offices.

In the 2023 parliamentary elections, the New Left coalition (SLD, Wiosna, and Razem) received 8.61 percent of the vote, with the left-wing presidential candidates eking out little more combined. There are 26 social democrats in the Sejm today, which is 190 fewer than at the beginning of the century. Why, in an increasingly secularizing and increasingly tolerant society, is there such low support for leftist values?

Poles are indeed more and more tolerant and progressive in terms of worldview, but on economic issues they are closer to right-wing free-marketers.

According to an Ipsos survey conducted in 2024 for the More in Common foundation, over 60 percent of Poles support the introduction of same-sex partnerships. Almost half declare a positive attitude towards gay people. Polish society is also becoming secularized more and more rapidly. According to data from the 2021 National Census, 71.3 percent of Poles declared their membership in the Catholic Church, while in 2011 it was 87.6 percent, marking a significant decrease. The fraction of weekly mass attendees has dropped from over 45 percent in 2018 to 29.5 percent in 2022.

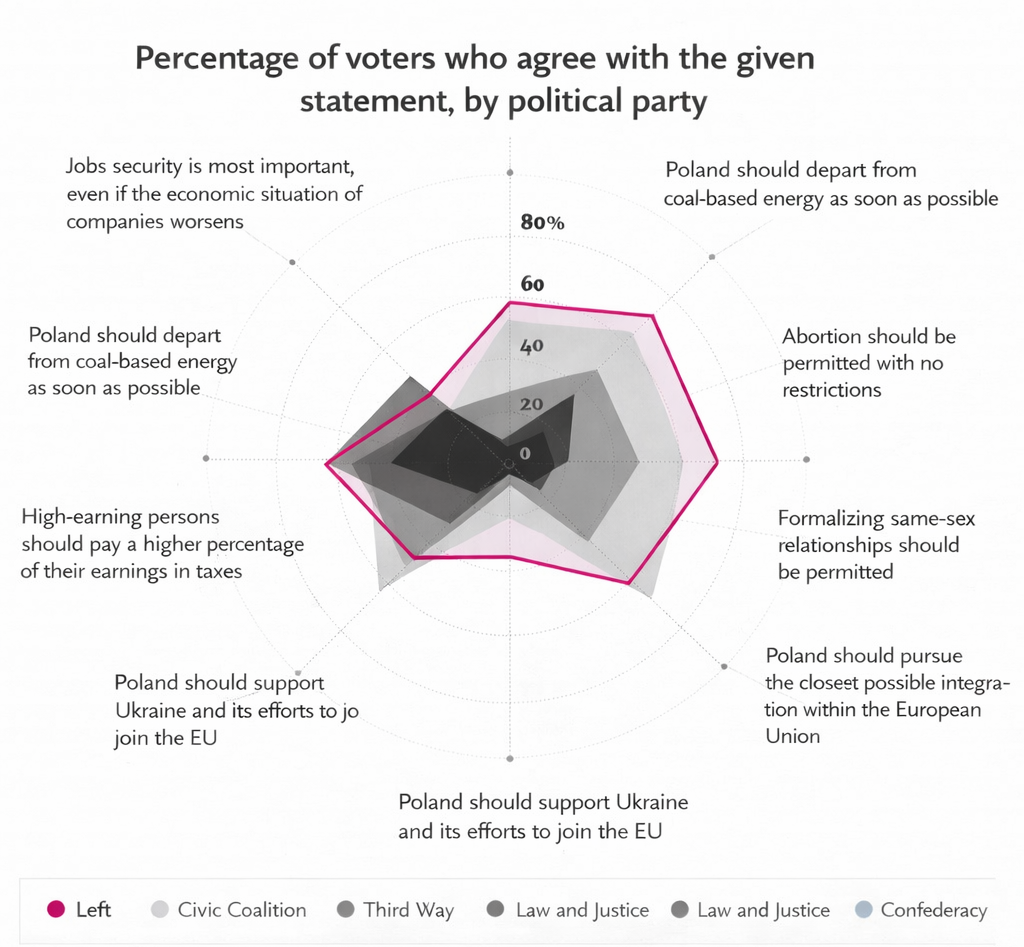

Source: Characteristics of the views of the electorates of the main political groups, CBOS, May 2025

The youngest generation of voters is the most liberal. According to a 2024 Ipsos survey for More in Common, as many as 65 percent of people aged 18-29 support relaxing abortion laws, including legalizing abortion up to the 12th or 24th week of pregnancy. Year by year, the percentage of non-practitioners and atheists among them is growing. Young people demand accountability for sexual crimes committed by clergy (much less often than the older generation). They show high support for civil partnerships, including same-sex ones.

According to CBOS data for 2024, about 50 percent of respondents are strongly against raising taxes, 36 percent rather against. Only 9 percent are in favour of raising taxes, and 5 percent have no opinion. At the same time, reducing state spending as a way to improve the financial situation is supported by as many as 72 percent of respondents.

Let us outline the context. In 2001, the socio-political situation was completely different than it is today. Poles opted for the left after four years of rule by the Solidarity Electoral Action and the Freedom Union (AWS-UW). The fall of Jerzy Buzek’s government was mainly due to reforms (including in health care, education, and local government), the effects of which aroused a groundswell of opposition. SLD vied for power with the promise of “normality”. But the practice turned out very different.

The governments of Leszek Miller and Marek Belka were shaken by a series of corruption scandals, the Rywin scandal foremost of them. Unemployment was growing. Despite its historical pedigree, which attracted many voters to the SLD, the left-wing government restructured the public sector, closed and privatized large factories, and cut spending on health care.

After four years, the left began its electoral decline, which continues to this day. In the presidential election, most left-wing candidates suffered embarrassing defeats. How did this happen?

Divorce or separation?

“The popularity of the Polish left was first cut off at the knees by Leszek Miller, with his irresponsible policy and a failure to implement what his voters expected from him, and then by Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz, the last politician who had a real electoral chance on the left,” says Dr. Łukasz Drozda, a political scientist and urban planner from the University of Warsaw, author of the books Dziury w ziemi. Patodeweloperka w Polsce [Holes in the Ground. Pathodevelopment in Poland] and Lewactwo. Historia dyskursu o polskiej lewicy radykalnej [Leftism. A History of the Discourse about the Polish Radical Left].

In his opinion, the results of the Polish left are also influenced by more universal, global trends. He explains that the increase in the quality of life in the countries of the Global North is not conducive to the popularity of left-wing movements, which traditionally direct their message to the most excluded and worst-off, and today, despite the many problems we still face, we no longer experience the conditions in which workers lived at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries or soon after the Second World War. At that time, socialist parties also benefited from something else: they took advantage of the fact that the extreme right, which also appealed to the people, was completely discredited. Today, these emotions no longer work,” says Drozda.

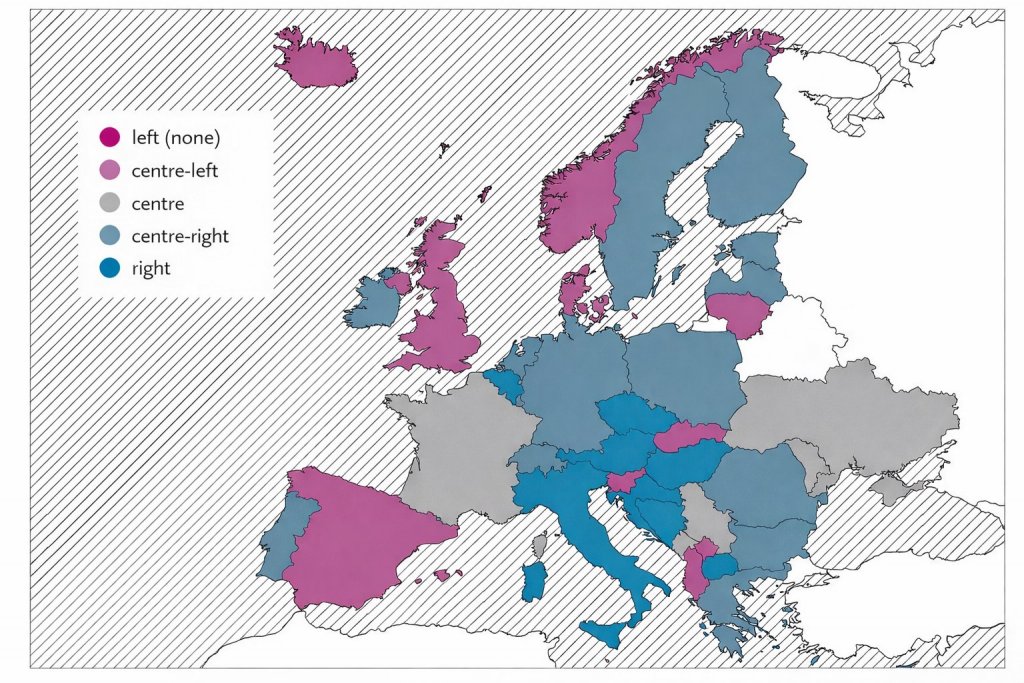

Right-wing Europe

Political identification of the parties currently in power

Source: in-house collation

According to political scientist Dr. Bartosz Rydliński, author of the report Separation or Divorce? The Working Class and Social Democracy in Poland analysing the reasons for the left’s poor showing in the 2023 parliamentary elections, the electoral troubles of the Polish left began when it cut itself off from its pedigree. In the 1990s, Rydliński explains, Polish society was divided into supporters of the post-Solidarity and the post-communist parties. The latter clung to the memories of the Polish version of the welfare state (a state in which the government actively intervenes in economic and social life, providing citizens with social benefits, health care, education, and support in the event of unemployment, illness, or old age), i.e. the People’s Republic of Poland. Their natural representative in the Third Republic of Poland became the SLD, which received their votes in great numbers at the beginning of the transformation. After 2001, it turned out that the party had disappointed its electorate’s hopes by pursuing neoliberal policies. “Today, hardly anyone remembers that just before joining the European Union, we had to deal with a number of socio-economic sacrifices,” says the political scientist. “Workplaces were closing. When the shipyards in Szczecin were going under, Leszek Miller said that his hands were tied, because the European Union requires competitiveness for accession. This had an impact on SLD’s ratings, in addition to the scandals of the Miller and Belka administrations. Throughout Europe, the neoliberal doctrine reigned supreme. Among social democrats, everyone believed in the ‘third way’, it was cool to blend socialism and neoliberalism.”

Abandoned by the left in this way, the voters were swayed by the Law and Justice party (PiS). Rydliński recalls sociological surveys from 2004-2005, which showed that even then the electorate identifying as left-wing mostly declared support for PiS. The party, headed by the Kaczyński brothers, took over the narrative of a solidarity state – in opposition to a liberal one, initially represented by the SLD, and after 2005 by the Civic Platform (PO).

Who is still on the left after that? For several months, I met with the left’s voters. The presidential campaign was underway. Most of my interlocutors declared that in the first round they would vote according to their conscience: for a leftist candidate.

Caviar or armchair?

I am sitting on the terrace outside of a suburban house near Radom with Henryk Milczarski, a pensioner, former industrial worker and trade unionist. Next to us, his wife Bożena smiles gently. She addresses her husband, with whom she shares political views, exclusively with the pet name “Heniutek”. We drink coffee. A moment later, dumplings are served (stuffed with meat and fried, just like mom used to make). We break the ice talking about books, because the Milczarskis read extensively and passionately, and recently Henryk has read through the whole Bible. “If the most hardcore Catholics read the New Testament at least once, I think the world would look different,” says Bożena. “The good of the Gospel is pure leftism.”

In the most recent campaign, they supported Magdalena Biejat. They believe that were it not for Zandberg’s run and the competition between the two candidates, her result would have been much better. According to them, leftism and the Catholic faith are not mutually exclusive. “I grew up in a home of believers, but not excessive ones,” says Henryk. “My mother would say: ‘If you want to go to church, then go. You don’t want to, don’t go.” Dad used to go, but not every Sunday. No one forced us to believe, there was no pressure, it was our conscious choice. That is why today we are closely connected with the Jesuits.”

Bożena is a member and deputy director of the Pope’s World Prayer Network in Radom. Henryk is not a member, but he is an advisor, organizes pilgrimages, and keeps a chronicle. Formally, it is a foundation operating at the behest of the Pope, whose task is to disseminate the papal prayer intentions. In Radom, the network organizes pilgrimages to places of worship, and every day at 8:00 a.m. it meets for prayer in one of the churches. The intention for August prayer is: “Let us pray that societies where coexistence seems more difficult might not succumb to the temptation of confrontation for ethnic, political, religious, or ideological reasons.”

Milczarskis in their home in Radom

According to the Milczarskis, the right wing and part of the clergy divide people into “real Poles-Catholics” who voted for Mr. Nawrocki for president, and the almost 10 million “non-Poles, non-patriots, non-believers” who voted for Rafał Trzaskowski. “Our family does not intend to change the fact that we are leftists,” says Bożena. “For us, leftism means helping others, empathy, tolerance, personal freedom, freedom of speech, religious liberty, and separation of the Church and state. But also openness to people regardless of skin colour, religion, country of origin, or sexual orientation. Social justice and equal opportunities for all citizens, regardless of wealth. Hadn’t someone already spoken about the same thing over two thousand years ago?”

Henryk was shaped by the values passed down from generation to generation. First by his parents, then by older friends whom he met early on his way. “My grandfather, Józef Wolski, my mother’s father, was a member of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland from a leftist party, the mayor of the Potworów commune, and a banker. He and his two brothers were in combat in 1920, for which one of them was granted land in what is now Ukraine. The family fell victim to the Volhynian massacre,” says Henryk. He claims that he holds no resentment for the harm done to his ancestors. “You know, our generation grew up on books and films in which Ukrainians were portrayed badly, like Jan Gerhard’s Łuna w Bieszczadach. We were steeped in it. But today we know that not everyone was bad, not everyone was in the UPA. We are not against Ukrainians, we know them, we have worked with them.”

Henryk’s mother was active in trade unions, in the works council. His father taught him patriotism and empathy towards others. Both Milczarskis learned sensitivity in their homes. Bożena’s family also included Polish patriots who fought in uprisings and were sent to Siberia.

Immediately after graduating from an electrician trade school, Henryk found himself in Radoskór, a huge plant producing shoes for the Polish and Soviet markets. “I met my mentors there. They were people 20-30 years older than me, who had a huge life experience. They had survived June ‘56, March ‘68, December ‘70 [dates of countrywide protests and crackdowns]. And they believed in me. They suggested: ‘do this, do that’. They did not teach me how to be obedient. They introduced me to the world of politics, social activism, helping the weak. They taught me cleverness.”

At the beginning of the 1980s, the resourceful Henryk and his colleagues founded a local “Solidarity” trade union, and he became the youngest shop steward and the youngest works council representative in the history of Radoskór. Works councils, although formally not independent but subordinated to the authorities of the People’s Republic of Poland, were treated as the voice of the labourers in talks with management. They mediated in disputes concerning social matters (allocation of holidays, vouchers, Christmas packages, etc.), or in matters of work organization. Henryk knew how to talk both with his colleagues from the shift and with the directors in elegant offices.

He winks and admits: in June ‘76 he went on strike with his friends mainly to brawl. He agrees that after martial law and a few years of General Jaruzelski’s rule, “Solidarity” was no longer the same as in its heyday. Milczarski felt ready to really spread his wings in a real, left-wing movement: the Polish Socialist Party, reactivated in the underground, founded by, among others, Jan Józef Lipski and Piotr Ikonowicz. After the Round Table agreements, the “new” PPS began to operate officially, and in 1993 Ikonowicz was elected a deputy to the Sejm. Henryk was in the PPS until it split at the end of the 90s.

The Milczarskis saw the effects of economic transformation with their own eyes. Factories transformed into state-owned companies brought losses and were eventually closed. Those that were privatized had to cope with brutal conditions of free competition, so they often laid off employees in droves. Shock therapy caused people to lose their jobs overnight without knowing how to do another. Many workers in Radom reached for the bottle, many ended up on the street. The Milczarskis remember times when they brought hungry people home. They cooked them dinners, sometimes gave them money to survive. There were those who came back for help regularly, for many years. “The workers who took part in the strike in 1976 felt embittered and disappointed, because they were the first to fall victim to the transformation,” says Henryk. “They thought that at their expense some people made their careers. They were fed up with ‘Solidarity’, Wałęsa, and others. They were the ones being evicted, hungry, and excluded. They were the ones who died from suicide, because this was not the Poland they’d fought for.”

Henryk changed jobs from Radoskór (which declared bankruptcy a few years later) to RADPEC (Radom Heat Energy Company), where he worked throughout the 1990s. Then he found a job in a completely different industry: a large Scandinavian company handling protection and security of mass events. He worked on securing Euro 2012. Over time, he began to train people and manage entire teams.

Throughout all these years, the Milczarskis have not been tempted by right-wing populists, they always voted for the left. But they know people who had been members of the Polish United Workers’ Party and were loyal to the People’s Republic of Poland, but after 2005 came to believe the promises made by PiS. In this respect, the Milczarskis agree with political scientist Bartosz Rydliński: Kaczyński’s party seized an electorate that longed for the welfare state and felt betrayed by the SLD and its neoliberal policies.

Henryk says that that old SLD was a “caviar left”. The politicians who came to power at that time felt that they could get away with anything – ransacking the public purse included. The working class, lower-level workers, small entrepreneurs, and farmers ceased to matter to them. Their darling was the educated manager, the stockbroker. And then, Henryk explains, they handed over power to young guns, such as Wojciech Olejniczak and Grzegorz Napieralski, who had nothing to do with the working class and its problems. “Only the merger with Wiosna brought a breath of fresh air, it combined the seasoned with the young. Now it is clear that the experience of Włodzimierz Czarzasty along with the strengthening of the rank-and-file are having an effect, we are starting to matter. Although things are far from perfect.”

Despite everything, Milczarski could not imagine voting for the national-Catholic right. In the new Poland, he first chose the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland (SdRP), then the SLD. Today, he is voting for the New Left (SLD + Wiosna), which made a difficult decision: it compromised and entered the government, and now it is gradually advancing its proposals, such as a widow’s pension or support for caregivers of people with disabilities.

The Milczarskis have four adult children. Przemek, the youngest son (born in ‘94), is a person with a disability and required care from early childhood. For years, the Milczarskis, together with other parents, fought for an increase in the allowance and the abolition of the absurd ban on paid work for caregivers. It was they, among others, who were going to the Sejm for years, protesting, sending letters and petitions to politicians for some relief. Only the minister from the New Left did something about it. In January 2024, the care benefit increased by PLN 530 (from PLN 2458 to PLN 2988 per month), and from January 2025 by another PLN 299. Another important change is the possibility of combining care with gainful employment, which was previously not allowed.

I ask them about personal assistance, a project that has long been stuck in the government’s legislative gears. In the summer, people with disabilities and their caregivers protested in front of the Chancellery of the Prime Minister. At that time, they heard an assurance from Minister Agnieszka Dziemianowicz-Bąk that the bill was ready and would be voted on by the Sejm this autumn. It stipulates first of all that personal assistance will be financed mostly by the state (so far it was mainly by local governments), and any person with a disability aged 13 to 65 will be able to apply for an assistant (in some cases, seniors will also be entitled to assistance). “This is a very necessary project,” say the Milczarskis, “and it is very good that it will finally be voted on. Better late than never.”

The Milczarskis do not have a good opinion of the Razem Party. For them, it is the “armchair left” that criticizes everyone but has little influence on reality because it has chosen to remain in the opposition. Nevertheless, they are optimistic. “The young generation of the left is the driving force of public life,” says Henryk. “A perfect example is the Vice-Voivode of Mazovia, Patryk Fajdek, born in ‘95, a hard-working man, a politician who not only knows how to speak so that others listen, but above all is himself an attentive listener. I’ve had the opportunity to have many interesting conversations with him, you know, I even feel like his informal advisor.”

The Milczarskis are convinced that it is the young people who will change the left from within. “This new generation is better than ours,” they say. “They are open, independent. And they do not get caught up in deals and trades like people did in our time, ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’. They are free to do and say what they want. Can’t say a bad word about young people.”

Like neighbour to neighbour

It is the young who break the mould of a left-wing voter. The survey Disappointed with the state, satisfied with life. Young Poles at the presidential ballot, carried out on behalf of the Batory Foundation in April 2025, shows that the youngest generation of voters would like to see their lives improved where only a strong state can do so. The biggest challenges perceived by young Poles are, first of all, “improving the quality of health care” and “strengthening Poland’s security”. In the same survey, the young cite “the growing gap between the richest and the rest of the populace” and “climate change” among their biggest fears – in addition to migration and the war in Ukraine. At the same time, young people show a certain inconsistency, because they most often mention “reducing the cost of living” in third place, and as we know, improving the health care system is most often associated with the need to increase social security contributions and taxes.

From a survey by the Ważne Sprawy Foundation and More in Common, cited in the report of the Batory Foundation, another grim conclusion emerges: young Poles do not trust the state and feel left out in the cold. “The majority of young people (68%) feel that in crisis situations they cannot count on the support of the state and its institutions, but must rely on themselves and the help of family and friends. The belief that the government is not interested in the young and cares more about the elderly (according to 80%) does not help to increase ties with the state,” the report reads. And further: “Such a perception of the state by young people must be influenced by their assessment of the quality of public services. The negative assessment of the education system stands out the most, since that is the one young people have had the greatest contact and experience with.”

Those who identify as leftists are strongly in favour of tolerance and equal rights but are no less concerned about the inequalities between the rich and the poor, or the unsatisfactory quality of public services. They feel abandoned by institutions, they fear for their future. They would like the state to finally start working efficiently and effectively.

A wave of anger

Aleksander Roszczyk from Warsaw, born in ‘92, doctor of medical sciences and corporate employee, wants those things too. These days, he supports Adrian Zandberg. “In high school, I was a fan of [Janusz] Korwin[-Mikke],” he says. “It was mostly an expression of outrage at the system. What the Korwinists said seemed so simple to me: let’s reduce taxes and everyone will have more, if the state doesn’t work anyway, nothing bad will happen if you contribute less to it.”

Aleksander was certainly also influenced by his parents’ views and conversations with them. He says that his father always supported the SLD, but in a “liberal way” – he liked the party’s policy at a time when it emphasized the role of the free market and competition. “I think he was captivated by the trickle-down theory, according to which the better off the richest people are, the greater the chance that something will also make it to those from the lower levels of the social ladder,” says Aleksander. Raised in the Soviet Union, his mother combined two experiences: in her youth she was brainwashed, but she later worked in a company resembling today’s corporations. Thanks to this, it was easier for her to adapt to work and life in Polish capitalism after the political transformation.

Aleksander’s father in the ‘90s was one of those who tried their hand at small business. He would travel abroad in search of trade opportunities. In those times, a huge market functioned on the stands of the former football stadium in Warsaw. “My father travelled to different countries and from there he brought goods that were unavailable here. My mother was a typist, she transcribed documents. She did it back in the ‘80s in Lviv, her home city, where she met my dad. When I was a year old, my father had an accident, and since then he has been in a wheelchair, but he remained professionally active for a very long time. He ran a company producing wheelchairs.”

Alexander emerged from the Korwinist period slowly, in stages. One of the key steps was an interest in the activities of the Miasto Jest Nasze [City Is Ours] association. The excesses of tenement house owners, false heirs who took over real estate for pennies and then got rid of inconvenient tenants with the help of “cleaners” opened his eyes to a huge social problem in his home city. He began to get involved in the activities of the association, became interested in the issues of traffic, public transit accessibility for residents, problems with the dominance of cars, etc. In university, he and his colleagues also founded an association representing the interests of laboratory diagnosticians. He participated in meetings at the Ministry of Health. He spoke about the standards of education and professional regulations for laboratory diagnosticians.

Spurred by a wave of anger, he joined the Razem Party. “Andrzej Duda had won the presidential election. I understood that I need to do more than just vote, I must put some effort in,” he explains. As an activist in Razem and a doctoral student, he contributed to the local government policy programme in areas of health care, care for the elderly, and social policy. “Many people said that Razem is an ‘armchair left’. It did not look like that to me. It was a place you went to and made things happen. There’s a call for a protest? We came with flags, brought sound systems, took care of security, did research, wrote programs. Today, I am still a member, but I am not directly involved in the activities. I pay dues,” says Roszczyk and smiles. Why is he no longer active in the party? He admits he lacks the time. He works, helps his mother with business. But he does not rule out that one day he might return to politics.

Why does he think the left still has such low support? “Because it’s afraid to be explicit. You need to speak to voters clearly, stake out an unambiguous position and fight for it,” he claims.

“The left has managed to do some cool things in government, such as the widow’s pension. There is also talk of social housing. But a more ambitious plan is needed. Adrian Zandberg speaks of things that are compelling to me. For example, about security, but not only through the armaments industry, but also drug security, the fact that in the event of war we will have a shortage of key medicines. He talks about the need to build nuclear power plants. These are big ideas. The left should come up with more such things.”

“But it is Zandberg who refuses to join the government,” I interject.

“Yes. Because he knows that in the government you might take one step forward, but two steps back. Push through one small thing, like the widow’s pension, but on the other hand be forced to pass business deregulation because of the coalition agreements.”

He is referring to a high-profile project headed by Rafał Brzoska – one of the richest Poles, the founder of InPost – and his team, preparing a list of ideas for simplifying the regulations on businesses and corporations.

“How can one do big things while outside of the government and with a few percent support?” I ask.

“We repeat it like a mantra, but it is very important: by shifting the political discourse towards leftist propositions. Even with the support it has today, Razem is already effectively bringing up the problems swept under the carpet for years and forcing mainstream politicians to deal with them,” Roszczyk answers. “Besides, Razem and the New Left are the only political formations that are able to stop the fascist slump in politics and social moods. Unfortunately, the liberals have failed even in this. Or maybe they never were liberals?”

Roszczyk defended his PhD two years ago (The effect of selenium-enriched polysaccharide [Se-Le-30] isolated from the mycelium of Lentinula edodes on lymphocytes), which makes him a doctor of medical sciences, but not an MD. He did not want to become one, because he is an introvert by nature, and the medical profession – as he says – requires an easy bedside manner. He always dreamed of staying in academia. While a part-time PhD student at the university, he earned money as a laboratory diagnostician. However, combining work in the laboratory with classes at the university became more and more difficult. Part-time employment just did not cut it: the cost of living in Warsaw was too high.

Facing reality, he got a job in a corporation conducting clinical trials on drugs. “Eventually I understood that it’s nice to have a calling, but you also have to make a living. At universities, salaries are too low, and the earning brackets of a diagnostician were insufficient as well,” he explains. “Of course, in science, you can apply for grants, but often you have to write applications fitting the expected mould, play to the current trends. And the funds from grants mostly go to materials and reagents anyway. In the biological sciences, the equipment is often worth more than people and their work.”

Every day after work, Aleksander goes to his other responsibilities. He takes care of his parents. His father had recently suffered a stroke. “There was a period when I drove from my apartment to my parents’ every day for half a week. In the end, I decided that I would just move back, live in my old room,” he says. And after a while, he adds: “I am also saving for a down payment to a mortgage loan and looking for an apartment.”

Poland of 2025 is no easy environment for such endeavours. Getting a loan is hard and apartment prices are exorbitant. Aleksander is resigned to look for a place far from his parents and outside of his home city. “Warsaw is not an option, so I look in the outskirts,” he explains. “But I keep second-guessing myself. They say that prices are bound to fall, but I keep waiting and there’s no sign of them falling. I wonder, if I take a loan now and buy an apartment, will I be living there for the rest of my life? Or will I eventually need a bigger one? What then? Will I be saddled with a loan of half a million, while the apartment I want to sell is worth half as much? It’s terribly stressful. And it’s sad that after so many years of work, study, sacrifices, all I might end up having is a debt I’ll be repaying until I’m sixty.” [You can read more about the situation on the Polish housing market in the article by Piotr Wójcik, “Pismo” No. 9/2022 – editor’s note].

Although thousands of his peers are in a similar situation, the housing problem is not a top priority for the government, comprising mostly of those who acquired their first apartments in the previous era. “Recently, I have noticed something interesting: people older than me, who were previously completely in favour of privatizing everything and enthusiastic about the free market, now increasingly return to positive memories of the old times, when they worked, for example, in the cable factory in Ożarów or in the tractor plant in Ursus. It turns out that the experience of the People’s Republic of Poland was not so bad, at least in my family,” says Aleksander. “It is said that during the communist era, people waited a long time for their own apartment. It’s true, they waited up to 15 years, but then they bought an apartment for 10 percent of its value. Today, it takes 30 years to pay back a loan. It is also true that it was a system that was supposed to be based on the power of the working class, and in reality, it itself exploited and persecuted the working class. There were also the dark times of Stalinism. But on the other hand, after the Second World War, this system allowed people to start… living like people. There were large investments, huge housing estates were built. In the life of our parents’ generation, there was much less uncertainty about work or housing. Once you had children, your living standard did not have to take a catastrophic nosedive. Today, it does.”

Daria Futkowska sees the situation of young people in a similar way. I suggest that we meet in a shopping mall in Warsaw. My thinking is, we will have air conditioning if it is hot, and coffee cheaper than downtown, and there will be no problem with parking. The day before, Daria sends me a message: “The weather is nice, there must be a place in the area with a garden or at least a view of the sunny street. I wouldn’t want to stay cooped up in the noise and artificial light.”

She is so right.

I leave the car in the parking lot, my wife and child – in the royal gardens, and I enjoy the bright, clear day as I walk to a café on Krakowskie Przedmieście.

Futkowska, born in ‘87, lives in a village near Jelcz-Laskowice in Lower Silesia, works in Wrocław. We meet in Warsaw because that weekend she is visiting friends in Falenica.

She comes from Wałbrzych. She saw with her own eyes all that is stereotypically associated with Wałbrzych in the 1990s: the unemployment, the poverty, the bootleg pits, i.e. illegally created, makeshift mines from which ordinary people extracted lignite with hand tools. But she insists that the real Wałbrzych of her youth was much more complex. There is, among other things, the music school that educated many artists, and which Futkowska also graduated from. There is the Szaniawski Dramatic Theatre, which attracted spectators from Warsaw and Krakow. And there are the people from different parts of Poland, descendants of those who came from the East under duress or to make a living, just like Daria’s grandparents.

Her mother (now retired) was a teacher, then she had a break from work and changed jobs: she started editing textbooks and created teaching materials in education and rehabilitation of individuals with intellectual disabilities and autism. Father, an electrician by education, worked at the Wałbrzych Coking Works, then ran his own business. Her parents separated when Daria was seven years old, so she split her life between two homes, and in the summer, she often spent time with distant relatives in the countryside.

“I couldn’t afford many things that my peers had. Somehow, I didn’t feel it very much. I just realized at some point that I wouldn’t go to camp, my parents wouldn’t buy me skis or an additional language course. A PlayStation? Forget it,” says Futkowska. “On the other hand, I won a year-long French course as a prize in a singing contest. Because that’s what Wałbrzych was like – there were many opportunities, but not everyone knew how to reach for them.”

She studied well, graduated from a highly-ranked high school and from an upper-secondary music school in classical voice (she is a soprano). She also sang in a metal band. “My mother read a lot, she introduced me to literature, film, music. My dad, a scientific mind, taught me to appreciate nature, biology, even survivalism,” she says. “I studied classical and Polish philology, then some Russian, to learn the language. Later, I regretted that I didn’t choose biology or medicine. Maybe I would have a solid profession. But instead, I work in a corporation, in payroll. Specifically, I am a payroll project leader, which means that I design processes to be effective, simple, and functional.

“You ask what made me,” she continues. “Maybe it was that on the one hand I was rooted firmly in the mundanity of Wałbrzych, at a difficult time of change and instability. And on the other hand, I was opening up to the world.”

An important experience for Daria was volunteering, which she had to take part in as a junior high school student. Some of her peers helped in an orphanage, others in a retirement home; Futkowska chose a community centre in the area where she lived. There was a playroom there, open to all children. Daria’s duties included preparing dinner for them and organizing their time, encouraging play, coming up with games. There were children for whom this dinner was the only meal of the day, because their parents had been lying drunk for three days. “I tried to empathize with them. I learned that life can be rough. But the values I learned at home cannot be overestimated. Perhaps other people my age were not told by their parents: “don’t laugh at him, his life is harder”, as I was, but instead: “don’t play with him, he’s bad news,” she concludes. Her parents have similar views as she does today.

In the presidential election, she voted for Adrian Zandberg. She says that for her this choice was obvious. She is critical of the Civic Coalition government and cannot imagine that she could vote for someone who is part of it. Joanna Senyszyn? Although she agrees with her in some things, she does not feel that a politician from the post-communist SLD represents her interests. “This proved true when I heard that Senyszyn has six apartments and does not support the introduction of the cadastral tax,” says Futkowska.

She values Zandberg for his consistency. He has stood by the same values for years. “I also don’t like the political gobbledygook, shouting matches during debates. It puts me off. Zandberg does not get into such squabbles,” Daria opines. “Plus, I have the impression that his views are supported by years of experience, work, scientific evidence. You can see that some intellectual work has been done there. He represents more than just fawning to the latest opinion polls.”

Maybe that is why, after moving house, she began promoting ideas to make life easier for her and her neighbours. She noticed, for example, that they all commute to the nearby train station by car. Each on their own, at the same time, to catch the same train. So, she set up a discussion group on Facebook where the people of her town can organize carpools. “I think it was a novel idea for some that it’s no shame to make an appointment somewhere at an intersection and go to the train station together,” says Daria. “I have the impression that such small things let us know that we can rely on each other.”

She also noticed that there are many young women living in her village who walk around the neighbourhood with prams. She suggested that they get together in the village common room. Her children have already grown out of it, but new mothers from her village still gather there. Daria, speaking from experience, says that spending time together like this is what these women badly need. It allows them not to feel lonely, pushed to the margins of social life.

When she had her first child, she discovered her own neuroatypicality. Before, she thought that she could do anything, that she was indestructible. With a baby daughter, she noticed that her ability to process incoming stimuli, the extents of her mental and physical endurance were finally exhausted. Motherhood made her realize that she can let go sometimes. Be a little kinder to herself. “Very late in life, I also found that community is one of the foundations of mental health,” says Futkowska.

Hormon przynależności

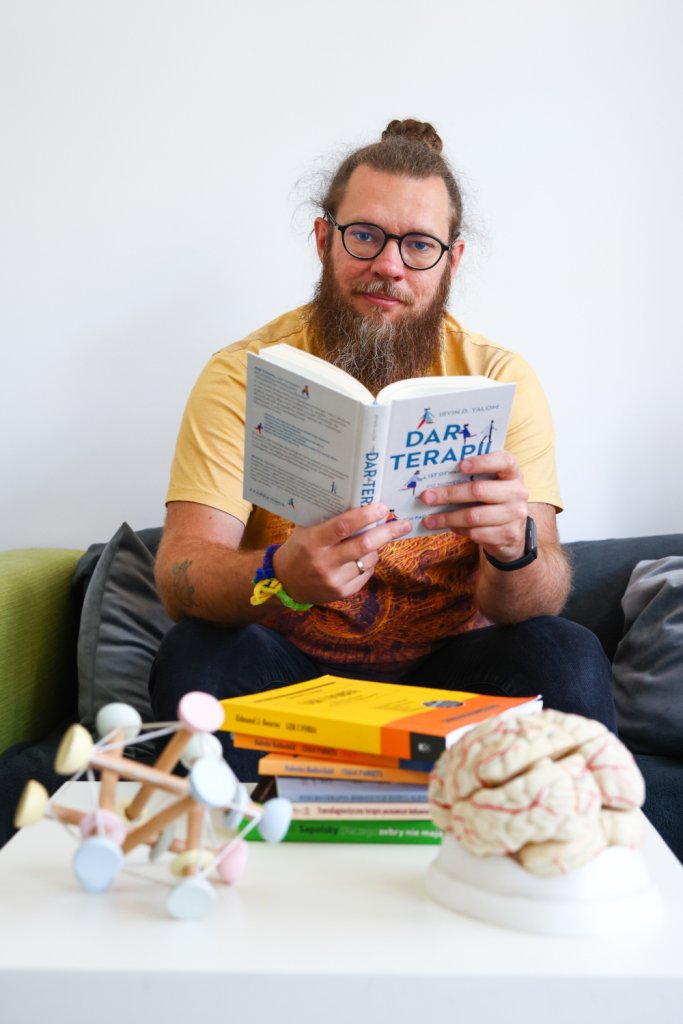

Karol Piasecki, a psychologist and therapist, explains to me how one affects the other. We meet in Bydgoszcz, in his office, on a break between sessions.

He cites the theory of Paul R. Gilbert, a British clinical psychologist and co-author of the book Mindful Compassion: Using the Power of Mindfulness and Compassion to Transform our Lives. According to it, a person has three systems of emotional regulation: the threat system, the drive system, and the soothing system. The hormone that rules the last of these behaviour-controlling systems is oxytocin (also called the attachment hormone) secreted, for example, by newborns as they suck on the mother’s breast. “Oxytocin,” the psychologist explains to me, “in adult life is secreted when we are among people. It gives a sense of belonging, community. So, it turns out that evolutionarily a human is adapted to living in a community. Not to constant competition.

“Most of us are turning away from community, going in the direction of selfishness,” Piasecki claims. In his opinion, since the beginning of the 1990s, the name of the game in Poland has been individualism: economic liberalism, the free market, and the I-got-mine attitude. “But are we really happy with it?” he asks rhetorically. “For some reason, there are more and more depressive and anxiety disorders. For some reason, the number of suicides is increasing. I see this in my personal experience and practice as a therapist. My clients are not people who turn to therapy because they want personal development or ‘wellbeing’. Most come to me because they suffer. And much of this suffering stems from a missing sense of community.”

Like several other interlocutors, I found Piasecki on Facebook, in a discussion group dedicated to the podcast Dwie lewe ręce [Two Left Hands]. It is a show created by Jakub Dymek, a journalist and publicist, past contributor of “Krytyka Polityczna”, and Marcin Giełzak, a historian by education, author of several books, and a former entrepreneur who ran crowdfunding campaigns on social media. Over a short time, the podcast, in which Giełzak and Dymek often have conversations lasting several hours, has gained tens of thousands of listeners. So, the leaders of left-wing parties are well advised to take into account the hosts’ opinions.

“Most of us are turning away from community, going in the direction of selfishness,” Piasecki claims. In his opinion, since the beginning of the 1990s, the name of the game in Poland has been individualism: economic liberalism, the free market, and the I-got-mine attitude. “But are we really happy with it?” he asks rhetorically. “For some reason, there are more and more depressive and anxiety disorders. For some reason, the number of suicides is increasing. I see this in my personal experience and practice as a therapist. My clients are not people who turn to therapy because they want personal development or ‘wellbeing’. Most come to me because they suffer. And much of this suffering stems from a missing sense of community.”

Like several other interlocutors, I found Piasecki on Facebook, in a discussion group dedicated to the podcast Dwie lewe ręce [Two Left Hands]. It is a show created by Jakub Dymek, a journalist and publicist, past contributor of “Krytyka Polityczna”, and Marcin Giełzak, a historian by education, author of several books, and a former entrepreneur who ran crowdfunding campaigns on social media. Over a short time, the podcast, in which Giełzak and Dymek often have conversations lasting several hours, has gained tens of thousands of listeners. So, the leaders of left-wing parties are well advised to take into account the hosts’ opinions.

When I interview him in his office, Piasecki is dressed casually: jeans, a T-shirt, and sneakers. I imagine that, as a therapist, he immediately inspires trust. “I’m not an ideologue,” he declares from the start. “I try to think pragmatically. When I meet real people I work with on a daily basis, I see that some things don’t work the way they could.”

“For example?” I ask.

“Recently, there has been a lot of talk about deregulation. The message we are given is, let’s deregulate, give more freedom to entrepreneurs and the economic problems will be solved.”

Karol is referring to the government’s cooperation with Rafał Brzoska. At the beginning of 2025, Donald Tusk entrusted the entrepreneur with developing and presenting specific changes to the law that would simplify doing business and cut red tape.

“Maybe, instead of deregulation, we should talk about regeneration?” Piasecki suggests. “This is an approach that assumes that we look at a given problem with common sense and try to solve it in a way that it is as fair as possible for everyone. Deregulation means the dismantling of certain structures, weakening the role of the state. Regeneration is the rebuilding of structures. Not only state ones, but also social.”

“And more specifically?” I ask.

“Creating structures where we, ordinary people, can have a real impact on how things are done,” he explains. “Say we have the idea to redesign the Jagiellonów roundabout in Bydgoszcz – maybe it is worth asking the residents of Bydgoszcz how they would like this renovation to go, what changes they want and which they consider detrimental? This is what regeneration is all about.”

According to Piasecki, a similar approach can be taken to solving the crisis in psychiatry. This is a problem that he himself faces on a daily basis. He says that in some private practices you only have to wait up to a few weeks to see a psychiatrist, but through the National Health Fund it takes several months. Access to child psychiatrists looks even worse. “There are simply not enough specialists. Why? Because the state cannot effectively encourage young people to choose a specific specialization after medical school. Regeneration is about creating such incentives. Looking at the needs of society and trying to intervene. So that a problem can be solved systemically,” he explains [Aleksandra Warecka wrote about the state of Polish psychiatry in “Pismo” No. 10/2021 – editor’s note].

One of the discussions held on the Facebook group of Dymek and Giełzak’s podcast has been about public transit. “On this front, Bydgoszcz and Toruń lack any sort of coordination,” Karol Piasecki tells me. “As a psychologist and psychotherapist, I see that living in a transit desert exacerbates mental problems, especially in young people. Imagine a person aged 14-15 who suffers from depression. Living in a small town, outside a big city, they have to get up around five in the morning to be able to go to school in Toruń or Bydgoszcz. After school, they have to hurry to catch the bus back or they’ll be waiting for hours, since suburban transit goes very rarely. Such a person is tired, does not get enough sleep, has no social life because they run to the station right after the last class. They come to me for therapy from time to time, but completely exhausted and only thinking about catching the next bus.”

An almost reflexive response of many politicians to the transit crisis is… even more free market, putting public transport in the hands of private carriers to sort it out through competition. According to Piasecki, they should do the opposite. Where the market has already failed, the state should intervene. Create a public transport system that would connect the countryside with the cities.

Piasecki admits that he did not always think this way. Once, he was more on the right, closer to libertarianism of the Janusz Korwin-Mikke variety. He grew up in the ‘90s, in the omnipresent cult of entrepreneurship, of taking matters into one’s own hands. His family home lacked no essentials, but it was no lap of luxury either. His parents – mother was a nurse, father a paramedic – had to be resourceful to make ends meet. They supplemented their budget by growing tomatoes and cabbage on a plot of land outside the city. On weekends, a sleepy Karol drove to the farmers’ market with his father to sell the produce. “My first memories and experiences are of my parents going to work farming vegetables after being on duty all night at the hospital. Of my mother saying not to throw away the plastic bag from lunch, because it can be reused tomorrow. So, they were taking matters into their own hands, but also caring about others and saving up,” he concludes.

His views were influenced by his work as a psychotherapist. In his office, he learned what those who have not succeed in life were struggling with.

Piasecki also works with adults who struggle with a difficult financial or professional situation. And this, in his opinion, directly results from the system in which they function and the role the state plays in it. “Young mothers come to me on the verge of parental burnout, with depression, stretched thin between raising a child, working, and taking care of the house,” Piasecki enumerates. “These are not problems that can be solved by the free market. We know what solutions are needed: facilitating hybrid work, enabling part-time employment but without cutting salaries, improving bonus systems, or introducing sick leave for sole traders. Today, if such a person breaks a leg, they simply have little to no income.”

Social sensitivity and empathy – these are the qualities that Piasecki wants to instil in his children. “One time, we were sitting at the table and I noticed that my son had stolen food from his sister’s plate,” he says. “I told him not to do that. If he wants more, ask me or mommy. Look to his sister’s plate only to see if she needs anything.”

A Catholic on the barricade

On the Facebook page of Piotr Ikonowicz, he found an ad: if you want to get involved, come over, you are welcome. And so, he went. At the headquarters of the Social Justice Office, they asked him if he was a lawyer. He is not. “And what can you do?” “I can spiff up your social media”. That is how he started. It was 2022.

He is an Internet whiz because before he came to Warsaw, he was into e-sports. He was part of an amateur team with his friends, took part in tournaments competing with other teams of gamers.

Instead of clashing with characters from computer games, he now takes on bureaucracy and inhumane regulations. “I didn’t realize before that there was such a housing crisis in Poland,” admits Maciej Niedźwiedź, a volunteer at the Piotr Ikonowicz Social Justice Office, 32, a chef by profession.

Before he became associated with Ikonowicz’s movement, he was not aware that tenants’ problems had not ended with the reprivatization scandal and the parliamentary investigative committee that followed. He did not know that in the capital of a European country you can throw a person out of their home and sentence them to live in a poorhouse or on the street. He also did not know the concept of “illegal eviction”. “A person who, for whatever reason, does not pay rent, is often thrown out of an apartment into the street, even though no court has decided the case. And it is done in many different, often brutal ways,” he says. “Let’s say that I, as a tenant, fail to pay rent for several months. Why? Life happens. Maybe I lost my job, got seriously ill, fell into a debt spiral. The owner of the apartment should go to court, which would issue an eviction judgment based on the evidence and decide whether I am entitled to social housing or not. But in Poland, such a procedure drags on for months. So, I’m waiting for social housing, but I’m still not paying rent. Some landlords decide to take shortcuts.”

Instead of waiting for the mills of justice to finish grinding, landlords reach for extrajudicial means. Frustrated by the weakness of the state, they turn to the free market for a solution. “There are companies in Poland that offer services in such situations. Let’s call them negotiations,” says Niedźwiedź. “It starts with harassing phone calls. Veiled threats escalate to serious ones. They glue tenants’ locks shut or take doors off their hinges.”

He recalls a case when a few hulking men one day “moved into” a woman’s apartment. They simply showed up with luggage and a rental agreement signed with the owner of the premises. The woman nevertheless decided to stay in the apartment with the “guests”. But some time later they decided to renovate the bathroom. By taking the toilet out of the apartment.

Why do people fall behind on rent? How do they get into trouble, ultimately falling victim to “illegal eviction”? “The reason is always the same: poverty,” says Niedźwiedź. It is unemployment or a job paid so low that, in the event of a sudden illness or such, there is simply nothing left for current bills. Another scenario: someone lives in a tenement house that needs to be additionally heated with electricity. In cold winters, bills run into thousands of zlotys per month. Some landlords agree to wait for the rent for a month or two, but others immediately say “goodbye”. Debts incurred by the poorest are also a common cause. People try to solve one financial problem with another loan, often a payday loan, because they hope that things will work out somehow.

Odpowiedzią – zdaniem Niedźwiedzia – powinien być program budownictwa społecznego. Ale nie widzi u polityków woli, by taki program wprowadzić. – Gdyby taka wola była, to mieszkania społeczne już by The answer, according to Niedźwiedź, should be a social housing construction program. But he does not see the will in politicians to make it happen. “If there was such a will, social housing would already be underway,” he says. “In Vienna, where a social housing program has been introduced, there is no housing crisis. And in Poland there is. Why has none of the parties decided to solve it over the years? I can’t answer this question.” [Elle Hunt wrote about Vienna’s housing policy in “Pismo” no. 2/2021 – editor’s note]

We are talking just before the first round of the presidential election. Adrian Zandberg and Magdalena Biejat raise the housing crisis issue and the need for social housing in their campaigns. But Biejat and the New Left, which forms a government with Donald Tusk’s party and the Third Way, failed to convince coalition partners to support this proposition. “As people of the broadly understood left, we have many interesting solutions to offer to working people. The problem is that we do not direct our message to them,” Niedźwiedź argues.

“Have you recently seen a left-wing politician speaking to a worker? No. The right-wing directs its message to working people. And it does so effectively.”

He arrived on the left in a roundabout way. Earlier, he favoured the circles of the Obywatele RP, KOD, and Lotna Brygada Opozycji [pro-democratic, centrist, anti-PiS organizations and initiatives – transl. note].

Five years ago, he moved from his hometown of Poznań to work in Warsaw (he says only that he made the decision to move spontaneously: he came on a trip and fell in love with the capital). On the 10th each month, he watched on the Internet and TV as flowers were laid at the monument commemorating the Smolensk disaster on Piłsudski Square. He saw that Lotna Brygada Opozycji [Opposition Flying Squad], an informal group of opponents of the United Right, was organizing its counter-demonstrations there. Eventually, out of boredom and curiosity, he went to see it himself. “I was surprised by how warmly I was received,” he says. “The famous ‘Grandma Kasia’ [an activist known primarily for civic protests against the rule of the United Right – editor’s note] was there. That’s when I met her first. Since the Brygada was barred from the monument by the police, it built its own, from cardboard, under which it laid a wreath.”

Maciej stood to the side and just watched. At some point, police officers approached him and took down his personal information. As they explained, it was on the grounds of disrupting a religious celebration. “I realized that something is very wrong in this country,” says Niedźwiedź today. “I simply got scared. I was stopped and identified for the first time in my life, and only for standing there. Even the officer admitted that ‘nothing will come of it, but he has to write it down’. Another time, I was IDed in connection with a terrorist threat, although the police could not tell me whether we were the threat or not. It was terrible.”

He began to participate regularly, went to protests and demonstrations. “One day I was walking through the Ogród Saski park to Piłsudski Square. I immediately noticed that police were following me. As soon as a larger group of us gathered, they simply surrounded us. It happened more than once that they would surround us in a tight cordon and simply storm us. And it’s not a pleasant feeling when a group of policemen in full riot gear charges at you,” he recalls.

We meet in an office at 26 Elektoralna Street in Warsaw. It is actually the seat of two institutions: Ruch Sprawiedliwości Społecznej [Social Justice Movement] and the Social Justice Office. The first is a political party, the second – an organization that helps the poor and needy in legal emergencies, for example, tenants who are threatened with eviction.

The party and the association were founded by Piotr Ikonowicz, an almost cult figure on the left. A social activist, but also a journalist and politician, a member of the Sejm in 1993–2001 (he represented the Polish Socialist Party, ran on the lists of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD)), in the 1980s he was an activist of the democratic opposition. And he is a brother of Magda Gessler’s [a popular TV chef – transl. note].

The Social Justice Office blocks evictions, gives legal aid to tenants who have lost their homes, intervenes on their behalf in state institutions. It conducts social campaigns, organizes meetings and debates on tenants’ rights and on alleviating poverty.

Niedźwiedź has been a volunteer at the Social Justice Office for five years. His day job is being a security guard in a hospital. It enables him to have two days off to work in the Office after a 24-hour shift.

Before the interview, I look at his social media profiles. Two things immediately catch my eye. The first is support for Rafał Trzaskowski in the presidential election, announced by Maciej on Facebook. “Honestly, in the first round I choose the lesser evil,” he explains. “I’m just afraid of what could happen if Nawrocki wins. The most important thing for me is that PiS does not return to power. As long as that doesn’t happen, I’ll be relieved. My left-wing views can wait.”

I am also surprised by his bio on Threads: “Socialist. Catholic for whom faith is action.” I ask Maciej Niedźwiedź how he combines faith with left-wing activism. “I could hide the fact that I am a believer. But why should I? What would it change?” he answers. “Of course, this is not a popular position on the left. Some people are bothered by it, others are not. For me, all that matters is that the people I work with in the Office are fine with it.”

I ask him why he goes to church if he knows about the crimes priests have committed over the years. “I don’t believe in the Church, I believe in God,” he says pointedly.

He can be critical of the left. Because for him, leftism is also independent thinking. “Let’s take the issue of border security and migration. There are several camps on the left in this matter. According to one, no human being is illegal and anyone should be able to cross our border. I ask, if a person does not have documents, how can we know what their intentions are in coming here? If someone wants to apply for political asylum or international protection, there are embassies for that, consulates. In my opinion, the state is there to check those who would enter it. The state needs to be strong.”

My awakening

In Warsaw, I meet with Kama Siwek. When asking around in the climate activist community who I should definitely talk to, it is her name I hear. She is 30 years old, on Instagram she describes herself as a “Climate Guardian”. We talk in Gniazdo Centre for Climate Activism. It is a place created by representatives of various organizations: Youth Climate Strike, Parents for Climate, and Extinction Rebellion (XR). They differ in their methods, but they share a common goal: educating the public about counteracting the climate catastrophe.

We make ourselves coffee and sit in a conference room, empty at this hour. Kama tells me about the path she has walked being an activist.

She did not immediately get involved with the topic of climate change. She says that her activist awakening came in 2020 with protests against the persecution of LGBT+ people unleashed by United Right politicians during the election campaign. “I was deeply shaken by how much aggression can be directed at people who, according to some, deviate from our ideas about gender. But also, how aggressively state forces behave towards protesters on the streets,” she explains.

Even before she took part in the protests, she became friends with a non-binary person. She learned what problems and obstacles they have to face on a daily basis. “I didn’t know, for example, that before non-binary people enter a community, they have to make sure that they are safe in it,” says Kama. At the protests, she met more and more people, including activists with several years’ experience. That is how she came across the people from Extinction Rebellion.

XR is a movement founded in the United Kingdom in 2018. Their main method of action are peaceful demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience. In 2021, Kama Siwek joined the movement. “I really liked the fact that there is no vertical, hierarchical structure in Extinction Rebellion. When decisions are made, it is not by the majority, but by all the people in the group,” she explains. “It was then that I began to identify as a person with left-wing views, championing equality.”

At first, she worked in the XR media group. She handled Facebook and Instagram profiles. “In this movement, you get assigned tasks quite early, you have responsibility for something from the beginning. It’s very motivating. I got into the thick of it right away,” Kama continues. She admits that she had a privilege that many activists cannot afford – she did not have to work to make a living. “I was very lucky I got a job at Extinction Rebellion and didn’t have to work in copywriting or advertising like many of my friends,” she says. She was born and raised in Warsaw,

One of the first matters she took on was the transfer of land to the Oblate Order in the Świętokrzyski National Park (ŚPN).

In 2021, the government of Mateusz Morawiecki removed from the boundaries of the ŚPN three mountaintop plots of land located in the immediate vicinity of the Oblate Order monastery of Święty Krzyż in Nowa Słupia. The idea was for the order to conduct business activity in that area of over 1.3 hectares of additional land. Civil organizations, including Pracownia na rzecz Wszystkich Istot, ClientEarth Polska, the Dziedzictwo Przyrodnicze Foundation, and Extinction Rebellion protested against the decision. According to them, creating an enclave in the middle of the national park, excluded from restrictions on tourism and services, could be a lasting detriment to conservation. Today, it is reported that the plots are to be returned to the national park, the process of restoring them is ongoing.

XR activists hung posters in Warsaw parishes with the slogans “Seventh: do not steal” and “Scandal on the Holy Cross” explaining what is going on with the plots for the Oblates. Even before Prime Minister Morawiecki signed the decree, they and a broad coalition of social organizations co-organized a campaign “Don’t try to fool us”. Dressed as witches, associated with the Świętokrzyskie region, they gathered in front of the Ministry of Climate and Environment, where they handed the officials a letter of protest signed by 38 thousand people. “The world is on the brink of climate catastrophe. We need to protect wildlife, because that is a condition for our survival. Meanwhile, the Ministry of Climate and Environment treats national parks as a commodity that can be traded in the name of political gain. We will not allow this,” Kama Siwek spoke then.

They also organized happenings in front of the order’s headquarters. First, they honoured “dearly departed nature” in a spectacle resembling a funeral ceremony. Then, disguised as devils, they signed a symbolic pact with the government to give the plots to the order. After a protest in front of the Metropolitan Curia of Warsaw, right-wing portals called female XR activists “young Satanists” who “protested against global warming and the Catholic Church”. What made them think so? The activists wore heavy, dark make-up and dark outfits.

Wyświetl ten post na Instagramie

“Such events, especially those organized by Extinction Rebellion, always involve a lot of stress, a lot of adrenaline. Mainly because people’s reactions are unpredictable,” says Kama today. “What worries me more than potential aggression from people is a complete lack of reaction. And that happens. People roll their eyes and shut us out. Climate protests usually get lost in a torrent of other news and that frustrates me a lot. I understand that there are people who are more worried about how to make ends meet at end of the month. But they are also impacted by whether another coal or gas power plant will be built in Poland. Why? Because coal and gas power directly affect the water table. Last year, 120 municipalities in the country restricted water use. This means that the problem affects a lot of people.”

Kama believes that Poland’s energy mix (diversity of energy sources) should be distributed and civic. Distributed, i.e. based to a much greater extent on renewable energy sources, and not – as today – about 60 percent on coal. It should also be civic, i.e. rest in part on ordinary people also producing energy (for example, from solar panels).

Kama sees a clear division of roles here: it is the activists who have to explain to society why such solutions are good, and the politicians – to implement them at the legislative level. “The task of the left today is to present climate-friendly and socially friendly solutions,” she concludes. “The current system is leaky, and we are patching it with more gas-fired power plants. This is a very uncertain investment, because gas prices are volatile. Let’s stop building gas plants and reformulate the system for renewable energy sources. I hope that brave and knowledgeable people will come forward and take responsibility for this. The energy transition is underway, but it is still very chaotic. What annoys me the most about politicians is that they try to please everyone. And they propose things that are no good for anyone.”

She does notice pro-climate propositions in the programs of left-wing presidential candidates. But they do not always sound like she would like them to. “Magdalena Biejat talks the most about the need to develop RES. She also combines it with nuclear energy, which I do not fully agree with,” the activist continues. “Adrian Zandberg, in turn, thinks that we should make our system nuclear-based, which I don’t understand at all. Because, firstly, it will again make us dependent on importing raw material from abroad. And secondly, we still do not have the technology that would allow us to store and dispose of the waste from such a power plant. Besides, nuclear does not address the problem of water shortages. On the contrary, nuclear power plants require huge amounts of water for cooling systems.”

She admits the subject matter she works with can be difficult and complicated. Especially since the topic of climate change has only broken through to the general consciousness recently. “When I started working as an activist, I had to catch up a lot, educate myself. From geography lessons in primary school, I remembered that climate warming was a problem, but for the next 20 years it was not the number 1 topic in the media,” says Kama. “On the other hand, I know that this is not an easy subject to speak on. Climate knowledge can be very technical. It’s a huge challenge to translate it into a news report or a reel on TikTok. But we have to. It’s high time.”

Epilogue: is this the moment?

I check in with my interlocutors several days after the second round of the presidential election. I gauge the mood.

“My heart was breaking when I watched the friction between Adrian Zandberg and Magda Biejat in the campaign,” says Aleksander Roszczyk, the corporate employee from Warsaw. “The television debates in the first round did a lot of good. They brought urgent problems to the fore: the demographic catastrophe, housing, inequality. Unfortunately, by the time the runoff rolled around, it was all forgotten.”

After the second round, he realized how far Poland is from seeing the progressive agenda realized on such issues as civil partnerships, the rights of non-binary people, or migration policy. Trzaskowski’s position disappointed him, especially his drinking beer with Mentzen. According to Aleksander, Nawrocki’s victory bodes badly, because it means further dismantling of the state.

“I was struck by the words of publicist Witold Jurasz, who said that the right is more driven by hatred, and the liberal left by contempt. I think it might be the truth,” says Karol Piasecki, the psychotherapist from Bydgoszcz. “After the first round, I talked a lot with my friends, but also with people from my professional sphere. From what I heard, Jurasz was on to something. A lot of contempt is being vented. A lot of fingers are being pointed in an attempt to divert blame from the Civic Coalition.”

According to Piasecki, Zandberg behaved “masterfully”, clearly indicating what he expects in return for support: legislation, not sinecures. This way, Razem showed that it “wants no part of the horse trading”. “I just hope Zandberg doesn’t start coasting now,” says Piasecki.

“Is a new duopoly on the horizon: Razem and Konfederacja?” I ask.

“That wouldn’t be bad. These are the two forces that are actually different. They differ on substance, not just on who is the greater traitor to the nation.”

Probably the person most distressed by the election results was Maciej Niedźwiedź, the volunteer from the Social Justice Office, who strategically voted for Trzaskowski in both rounds. “For a few days, I gave up on our society, but I’m over it,” he reassures. “My opinion was that we must create a united front. If I were Adrian Zandberg, I would have supported Rafał Trzaskowski.”

Statistics show that 16 percent of Zandberg’s voters went with Nawrocki in the runoff. “There are people on the left who prefer to vote for the right, since its messaging is a little more social,” Niedźwiedź believes. “For some, voting for the liberals is a betrayal of left-wing ideas. Let’s remember that it was the PiS administration that introduced social programs such as 500+ [currently 800+, a monthly benefit of PLN 800 per child under 18 – editor’s note].”

“If Trzaskowski had won, it would have been the same for me,” says Laurie from Krakow when I ask for her assessment of the election result. “From my perspective, nothing changes. We will still be going abroad to have abortions, still tangling with Nazis in the streets. It’s a vicious circle in which we have been stuck for years. Nawrocki’s victory may have the upside that people finally wake up. That they notice that the rights of women, queer people, and immigrants are under threat, and maybe this is the moment to organize.”

Daria Futkowska has a scheduled induction interview into the Razem Party. What exactly does she mean to get involved in? She is not going to run for office, she is certain. “I’ll see what needs to be done. Anything that requires travelling, working in the field, I don’t have the space for,” she caveats. “But maybe they need someone to write something, record something, show up for an event. To me, party membership is most importantly about attending the meetings, expressing my opinion and my perspective, and voting in party-internal ballots, because then, even not being on the electoral lists, you still have a direct influence on who goes on these lists and what they propose.”

“When they ask who you are, what will you say?” I inquire.

“A normal person who works, earns an average salary, tries to live normally. And I’m a mom.”

Kama Siwek felt mobilized after the election. Now she hopes that Nawrocki’s victory will paradoxically strengthen civil society, grassroots movements, and non-governmental organizations. After the result was known, she posted a picture on Instagram with her own appeal to women and a mini-test.

“If it is hard for you, ask yourself: have you ever counted on politicians?” she asked. Below she included two possible scenarios. And suggestions how to deal with them.

“No? You know what to do. The same things you always did: support friends, help the weak, educate yourself and others. We will love each other and be friends, and that’s how we will save each other.”

“Yes? I’m very sorry. Remember that even if we don’t have a democratic president, if the government isn’t on our side, even if there are no independent courts or free media, we – the people – are still here. You are one of us. You are important.”

Text: Mariusz Sepioło

Photography: Beata Zawrzel

Editor: Magdalena Kicińska

Language Editor: Ilona Turowska

Proofreader: Tatiana Krajowska-Kukiel

Fact-checking, graphs: Marcin Czajkowski

Infographics: Anastasiia Morozova

Digital editing: Ewa Pluta