Where are you really from?

As the association between terrorism, Islam, and migration became a permanent fixture of the public imagination, and the term no-go zones was also becoming popular, I decided to check how much truth there was to all this and went to a place where – supposedly – only dangers awaited me.

It is February 5, 2025, 6:15 a.m. It is still dark. Both boys are only teenagers, one wearing a black hoodie, the other a white one. The video circulating on the Internet does not show whether their skin is dark or light. They are quickly walking out of the Clémenceau metro station in Brussels. The Kalashnikovs in their hands look like clumsily held plastic toys. Shots are fired, but no one is injured. The teenagers quickly return to the station, the recording ends. My first thought: “Terrorists?”

It quickly turns out that these were clashes between local drug gangs. The mini-war lasted for a few more days, the results: one fatality, several wounded. The last shoot-out in Belgium’s capital happened a few months ago. The port of Antwerp, an hour’s drive from Brussels, is the main entryway for cocaine smuggling from Latin America to Europe, with Belgian customs seizing 44 tonnes of the drug in 2024, down from a record 116 tonnes seized the year before.

Clémenceau station is located near the Brussels-South railway station, at the border of the communes (which can be compared to city districts, but with greater autonomy) of Saint-Gilles and the working-class Anderlecht. I get off the train there a few hours after the shooting. The surrounding walls are covered in graffiti, I catch the slogan “Free Gaza”, I pass a group of unhoused people, they speak Polish. The metro is closed while the investigation is underway.

“The area is very dodgy, be careful when you drive through there,” I hear from a Polish friend who has been living in Belgium for three years.

The label of “dodgy” has also stuck to the neighbouring commune of Molenbeek-Saint-Jean – colloquially known as simply Molenbeek. In the media, it was also called a “breeding ground for terrorists” – after the attacks in 2015 in Paris and a year later in Brussels at the Zaventem airport and the Maelbeek metro station, located right next to the European Parliament. Twenty- or thirty-year-old terrorists from the Islamic State, who organized and carried out these attacks, were connected with the Molenbeek area.

Even back in the election campaign of 2016, the current US President Donald Trump called Brussels a “hellhole”. “They want Sharia law, they don’t assimilate,” he demonised Muslims in an interview with Fox News.

The same arguments are used by European politicians in Belgium, France, Germany, and Poland who oppose immigration from African countries and the Middle East.

The association between terrorism, Islam, and migration has become a permanent fixture of the public imagination. The term no-go zones, promoted by Donald Trump and the media, which is supposed to mean immigrant districts in Western Europe where lawlessness and radicalism reign, has also become popular. When I search for information about the infamous commune, the titles of Polish articles pop up on Google: Molenbeek, a jihadist haven in the heart of Europe; Molenbeek: a quiet neighbourhood with an underground life of terror and jihad; Molenbeek – the “nest of jihadists” in Brussels attracts tourists.

How much truth is there in all this?

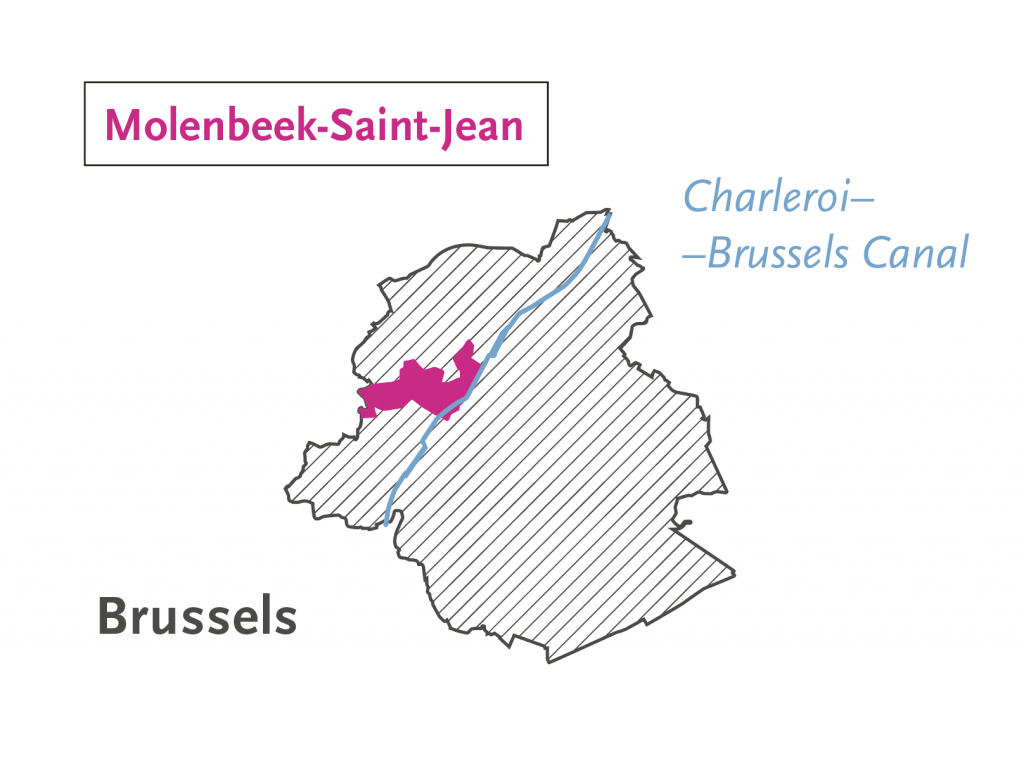

The Charleroi-Brussels Canal divides the capital region into its north-west and south-east parts. The region includes nineteen municipalities, among them the city of Brussels, which lies at the very centre. In the 19th century, thanks to the import of coal on a massive scale, the capital experienced rapid industrial development. Factories were established in northern and western communes, including Anderlecht and Molenbeek. The vicinity of the canal, which was used to transport raw material from other parts of the country, was very attractive for industry. Brussels’ industrialization peaked the twentieth century. Economic development after World War II caused Belgians to move to the service sector and into the eastern part of the city.

The demand for factory workers attracted immigrants from other parts of Europe, and, come the 1960s, mainly from Morocco and Turkey, under agreements to bring in labour. Initially, they came for a limited time, but many settled permanently and brought their families. As the Swiss writer Max Frisch famously wrote: “We were calling for labour, and instead people came.” Despite the successive deindustrialization in the following decades, those people’s children and grandchildren still live in former working-class districts, while immigrants from other EU countries and white Belgians have settled in the south and east of the country. Molenbeek is sometimes called “little Morocco” because of the dominant minority of this origin. Many of its members are now descendants of parents and grandparents who came to Brussels in the last century. If you look at the map, the city is divided in half in terms of ethnicity and class, as if it were crossed by an invisible line.

I walk from the Brussels-South railway station through the capital’s historic centre, where I pass groups of tourists obediently trotting, despite the bad weather, behind their guides’ umbrellas. I take the metro a few stops south, to the European Parliament, surrounded by a huge banner proclaiming “Democracy in Action”. A protest by industrial workers against the green transformation is staged nearby. There is even a delegation of the labour union “Solidarność” from Dąbrowa Górnicza, a Polish mining town.

Returning to my route, I pass a business district, where the brick facades of tenement houses are gradually pushed out by large, glass office buildings. Finally, I reach the canal, with Molenbeek on the other side. With every step into the district, the tangle of narrow streets deepens, and more and more tenement houses seem neglected – and no wonder, because as many as half of them were built before 1919.

Next to signs in French, Arabic ones appear, cafés give way to tea houses serving Moroccan-style drinks, with lots of sugar and mint. There are no tourists here, and there are also much fewer whites than in other districts. Churches are adjacent to mosques – Belgium does not keep statistics on the religious affiliation of its citizens, but polling data shows that in 2019 Molenbeek’s inhabitants were over 40 percent Muslim (in the country as a whole it is only 8 percent).

However, this is only part of the truth, because the district is as huge (inhabited by almost 100 thousand people) as it is diverse. It can be divided into two main parts: the western – slightly wealthier and the eastern – working-class. Further north, a few bus stops from the terminus of the metro line, Molenbeek resembles a separate, small town living at its own pace among red brick tenement houses. In the early evening, a little further from the main street, there is not a living soul on the sidewalks. In the only open bar in the area, three men are drinking beer, not their first, another one sleeps for a good hour on a bench under the scarves of local football clubs hanging on the wall. I book accommodation near the bar.

“It’s a very quiet and safe neighbourhood,” convinces me a French teacher and owner of the spacious apartment where I get a room. My local friends joke that I am spending the night at the end of the world, because for them, who live in the vicinity of the city centre, 40 minutes by bus is the suburbs.

The next day I go to the heart of Molenbeek, that is, to Chaussée de Gand street. Arabic music with a chorus repeating “habibi” from the nearby shops accompanies me in the background for the next several minutes as I walk. There are shops with richly decorated abayas, gilded tableware, crystal knickknacks for the house. Belgian bakeries, halal butchers and, of course, tea shops. I enter one of them, where I meet Hassan, who owns a restaurant with Arabic cuisine.

“I came to Molenbeek in 1999. Life is good here, but rising rent is a problem, so this year I moved to Ganshoren, even further north. All my neighbours are of Belgian origin, but I have never experienced any reluctance from them. I don’t think Belgians are racists. Even if you don’t have papers, but you don’t cause problems, no one will bother you. I know what I’m talking about because I’ve been through it myself. I was sans-papiers [French for “undocumented”] until 2004, all the time working in restaurants, because that’s what I did in Morocco. Now I have dual citizenship. 20 years ago it was much easier to legalize, but today too many people apply for papers,” says Hassan.

“And I’m not going anywhere. I have my favourite café here, my friends, in other districts I don’t feel as comfortable as here,” interjects his friend Morad, also Moroccan, who sits at the table with us and has only listened so far. He is unemployed because the factory where he worked for many years has been closed. So he lives on welfare, his family helps him survive.

There are many others in a similar situation. About half of Molenbeek’s residents aged 18 to 64 are unemployed – more than in other parts of the capital region. Revenues in the commune are well below the average in Brussels. This situation is due to several factors, including the unrelenting closures of industrial plants since the 1970s, to which workers from other countries were brought in – often with poor French or Flemish skills and only primary education. At the same time, the population of the commune is constantly growing, because it is often the first stop for more immigrants as they arrive. Almost 30 percent of the Molenbeek community does not have Belgian citizenship.

I ask whether the terrorist attacks of 2015 and 2016 have affected the lives of the commune’s inhabitants in some way. At first, both men deny it, but after a while Hassan opens up:

“We were furious with the people who did it because they came from our community, and that’s why we all had to pay for it with our reputation, even though we had nothing to do with the attacks. My wife is Dutch, our children speak French and Flemish. The younger son is 17 years old, still studying. I keep an eye on who he spends time with after school, I want to know who he is in contact with. However, I know that not every parent does this, which is why some teenagers can fall into bad company. But that’s not my problem anymore.”

Questions about the sources of radicalization are some of the most difficult. Contrary to what anti-immigration politicians and publicists say, it does not stem from culture – however we define it – but rather from a sense of injustice, directionlessness, and poor financial situation.

However, this is still only part of the truth. I am told more by Loredana Marchi, director of the Foyer organization, which has been operating for over half a century. Marchi is a legendary figure of Molenbeek – one of the bridges on the canal was named after her. Foyer fights the stigmatization of the municipality and its inhabitants on two levels: by supporting foreigners in preserving their culture, and at the same time by helping them in the process of integration into the host or majority society.

“Thanks to many years of experience, we fill in the gaps left by state authorities in this field,” explains Marchi, who is an immigrant herself. She came to Belgium from Italy in 1974. However, she does not want to talk about her experience because she thinks that it will not bring much to our conversation.

“Ten years ago, we noticed that more and more young people from Molenbeek were becoming radicalized. We looked for reasons and it turned out that the Internet was a huge factor. These kids have untapped potential, but they often have fewer opportunities than their peers from richer neighbourhoods, so they become easy targets for radicals. The problem is also inferior quality of education and poorer housing conditions than in other immigrant and working-class communes, like Schaerbeek or Anderlecht,” says Foyer’s director.

All this can be reduced to two concepts – class divisions and social inequalities. Didier Eribon, a French sociologist from the working class, writes about it in his book memoir Returning to Reims: “Selection within the educational system often happens by a process of self-elimination (…) as if the barrier between social worlds was utterly impermeable. The boundaries that divide these worlds help define within each of them radically different ways of perceiving what it is possible to be or to become, of perceiving what it is possible to aspire to or not.” [Translated by Michael Lucey]. According to administrative data, students from Molenbeek are more likely to choose vocational schools than their peers from other parts of the region, and generally do worse at school. And again, there are many reasons for these disproportions.

“I met teachers who rejected job offers in Molenbeek because they did not want to struggle with difficult teenagers. They are difficult because of poverty and the feeling of rejection by the rest of society, because they come from Muslim culture or are black. The case of the murder of Samuel Paty [a French history teacher who showed cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad from the weekly Charlie Hebdo in class] by a terrorist student is still vivid in their imaginations,” Nicolas Landmard, a former high school ethics teacher in the municipalities of Saint-Gilles and Uccle, now a local photojournalist, tells me.

This is how we fall into a vicious circle.

Arie Kruglanski, one of the most influential social psychologists, developed the current model of radicalization known as the 3N model (needs, narratives, networks). According to it, the process of radicalization is driven by three main factors: frustrations that prompt the search for meaning and belonging; narratives as ideologies that offer explanations for problems and justify the use of violence; and finally, the social networks reinforcing these beliefs.

According to the analysis of intelligence data from Western European countries – carried out by the economist Jan Zygmuntowski – people who joined the ranks of the Islamic State (ISIS) were most often men under 25 years of age, unemployed, with primary education, coming from poorer working-class districts and families with immigrant roots (all those who carried out suicide attacks in France and Belgium in 2015 and 2016 were of Moroccan origin, but they were second-generation immigrants – they were born here and had European citizenship). Teenage rebellion and identity crisis related to living in “one’s own” and yet still “foreign” country are also of great importance. In the Muslim community, there is also a sense of injustice resulting from the situation in the Middle East and from Islamophobia. These are exploited by ISIS or other terrorist groups, especially through propaganda spread on social media and YouTube. It is worth noting that a significant percentage among jihadists were converts, which confirms the thesis that the source of radicalization is not Islam itself, but rather a deep sense of frustration and external factors.

In Poland, too, post-industrial cities and districts have struggled – and often continue to struggle – with high unemployment, frustration, and radicalisation, especially among young men. Take for instance Radom and the double-digit unemployment that has persisted there for many years. The difference is that in the West, these inequalities are compounded by skin colour, which we experience much less often in our still monolithic country. Przemysław Wielgosz, journalist and publicist, author of, among others, Gra w rasy. Jak kapitalizm dzieli, by rządzić [Race Games. How Capitalism Divides to Conquer], tells me more about the fact that the processes of impoverishment and exclusion are common:

“The expansion of the capitalist economy, which has been progressing since the nineteenth century, creates new forms of class inequality, resulting from the process of proletarianization of the peasant population, which included its impoverishment. At the same time, representatives of this class, who came to the cities for jobs, first from the surrounding countryside, then from other regions, and finally from other countries, were from the beginning treated by the bourgeoisie and other privileged groups as strangers, emphasizing the differences between “us” and “them”. Those others from the countryside were replaced by immigrants or Muslims over time, but the scheme of exclusion remains the same: different means lower in the hierarchy. Inferior.”

In this light, can violence resulting from inequality be justified? Everyone has to answer this question for themselves.

The canal area is undergoing changes that worry the residents of Molenbeek, but I will find out about it later. Now I’m standing on the bridge and reading a stencilled slogan: “Exclusion is not the solution”. And then there are the stickers: “We are all looking at Sudan”, “Don’t stop talking about Palestine”. I sit down in Phare café located right by the canal. The menu includes vegan breakfast, fit brunch, fruit smoothie. In a fashionable, industrial interior, I hear conversations in French and English, several people work on laptops. I finish my coffee and run to meet the employee of Bonnevie – Maison de Quartier. It is a non-governmental organization dealing with, among other things, the fight for tenants’ rights in the Molenbeek commune and the surrounding area.

A few hundred meters into the commune, in the square in front of the church, like every Thursday, there is a market. Vendors, mostly men, shout over each other, flogging the wares: olives, Arabic sweets and spices, colourful fabrics, small kitchen appliances and electronics, fruits and vegetables. Customers, usually women, choose from a wide range of products. Most of them wear a headscarf and a long skirt. I squeeze through the crowd, pull out my camera. A middle-aged man accosts me, asking me in English not to take pictures out of respect for the local culture. I apologise for the misunderstanding.

“On the one hand, it is indeed a matter of culture, because some Muslim women do not want their faces to be photographed. On the other hand, the residents of Molenbeek are very distrustful of journalists, because the media have done them a lot of harm,” explains Cedric Vaessen, coordinator of Bonnevie. He himself had many questions and doubts before agreeing to the interview.

“Promise me that the term no-go zone will not appear in the title of your article,” he asked.

A few steps from the headquarters of the organization there is an elongated, concrete square with the Comte de Flandre metro station, the construction of which began in the 1970s. Lines No. 1 and 5 passing through here connect the east with the west.

“When the work on the metro network reached Molenbeek, the constructors intended to demolish residential buildings that stood in the way of new infrastructure, forcing people to move out. Residents and activists started a protest that gave rise to Bonnevie,” he explains. The concrete square is a scar that the authorities have left on the urban tissue. Cedric emphasizes that in the centre of the capital demolitions did not take place, though the same metro lines (and many others) run through there.

“Today, we are conducting consultations for tenants who are threatened with unlawful eviction. Migrants living here sometimes agree to very poor housing conditions for a high price because they have an unregulated status, and finding accommodation for people of non-European origin – even if they are Belgians – can be very difficult. Many landlords unscrupulously take advantage of their situation, and there is a shortage of social housing,” he says. Official data shows that the average waiting time for this type of apartment in the municipality of Molenbeek is over 14 years. At the same time, it is in places like this that they are most needed.

Cedric Vaessen, Bonnevie Coordinator. Photo Anna Mikulska

I also hear about double standards in the housing market from Ahmed Benamar, a middle-aged man who owns a grocery store.

“After 2015, we began to experience even greater discrimination in access to housing or on the labour market. There was no chance to find an apartment outside the district, because the current address made it impossible for us. Nobody wanted a tenant from Molenbeek,” he sums up, sipping strong tea with sugar and mint in a cramped, stuffy place near the square where the market was held.

I find similar stories on an online forum. People with immigrant roots in Brussels exchange experiences there, writing, among other things, about magically disappearing rental offers, regardless of high income and stable work: “I don’t see any other reason why homeowners reject us than our origin. Many of them tell us that they are impressed and that we would be good candidates, but then they ask: ‘Hey, you don’t look Belgian, where are you from?’ When they hear the answer, their smiles fade. Is it really a problem for these people that we are not Belgians by origin?”

“In theory, we all have guaranteed equal rights. The regulations exist, but they must finally be obeyed,” notes Ahmed.

Research conducted back in 2005 confirms that Belgians whose parents or grandparents came from Africa or the Middle East experience ethnic and racial discrimination in the labour market with the same competences as their white competitors.

The researchers point out that a similar situation occurs in the housing market – people with a non-Belgian surname were less likely to rent an apartment, regardless of their economic situation.

Right on the banks of the canal, old tenement houses are adjacent to new architecture; there are also small museums and a few cheap cafés, such as Phare. The process of gentrification usually looks similar: private investors put their capital in apartments. New, interesting spaces are created, the middle class move in wanting to rent cheaper apartments but still be close to the centre. There is also the creative class arriving, which makes the space even more attractive. In general, these processes increase the average income in the municipality, but they also have worrying effects – rental costs rise and new residential buildings become unaffordable for those who lived here before. The working class is being pushed further and further away – and this is exactly what Molenbeek is struggling with today.

On the one hand, the authorities of Brussels are proud of being the second city in the world, after Dubai, in terms of the number of nationalities – people from 184 countries live here. But if you look deeper, you will find that the capital is divided into small communities with different national and ethnic backgrounds.

Flemish (it is the second official language of Belgium, next to French), because – as he emphasizes – we all have a tendency to stay in our comfortable little corner. Friends who live outside Brussels worry that his work in Molenbeek is risky.

“I’ve never felt unsafe here, but I’ve noticed that even Belgians from Brussels don’t want to come here, because the bad reputation of the district has stuck,” he says.

“Maybe bringing Belgians here from other parts of Brussels will be conducive to integration?” I ask.

“In Bonnevie, we try to break down walls and fight prejudice through various initiatives, such as joint breakfasts. Although we are not dealing with segregation, crossing cultural boundaries is a really big challenge. Let’s look at the canal again – opposite Molenbeek there is a hipster housing estate, inhabited mainly by people of Belgian origin. They rarely come to the other side, for many it is a different world.”

Walking towards the “hipster housing estate”, in a small alley right on the bank of the canal, I chat up a woman smoking a cigarette. I ask where I can find the nearest grocery store. It turns out that she works at Carrefour a few minutes away, so we walk together. She’s from Morocco, about 25 years old, wears tight jeans and has uncovered hair. Previously, she lived in Spain, she moved to Brussels during the pandemic, although she does not know why.

“I don’t like this city. People are stressed, in a constant rush. But I feel good in Molenbeek because there are many people from my country here, although they are just much more reticent than in Morocco. You know, over there I could dress as I wanted, and here it happens that Moroccans insult me, they would probably even want to hit me, because I’m a woman who doesn’t dress traditionally. In Spain, Moroccans were much more open, I don’t understand why they are so traditionalist here. I don’t like it,” she says and laughs that she walks so far from the store for cigarette breaks because neither her bosses nor her co-workers know that she smokes, and they could make a fuss.

“I know that people say Molenbeek is dangerous, but the only threat I see is insults towards Muslim women who are more European,” she says, and then we enter the Carrefour and I buy a pack of Vogues. A shop assistant in a hijab hands them to me with a smile.

Maykel Verkuyten, a Dutch anthropologist who studies ethnic identity and cultural diversity, writes: “Minority members who feel unwelcome or discriminated against are likely to be less satisfied with their life in the country of settlement. They can also develop a stronger identification with their own ethnic group. Group identification implies a sense of belonging that might attenuate or buffer the negative effects of perceived discrimination on life satisfaction.”

“I was born here, but I have Moroccan citizenship. At that time, as a child of Moroccans, I did not automatically become a Belgian citizen, but I could legally live and work here on the basis of a residence card [French: titre de séjour – A.M.]. After the legal reform, I could easily get Belgian citizenship, but I don’t want that. I won’t be a Moroccan from Belgium,” Ahmed Benamar says proudly.

It is very difficult to determine the exact number of sans-papiers. According to research and estimates by Loredana Marchi from Foyer of Molenbeek, there are about ten thousand of them. This is a completely different category than people with international protection (mainly refugee status) or Belgian citizens of immigrant origin.

“They are a minority, but their situation is much more difficult and their opportunities are limited, which can lead them into crime,” says Marchi.

However, the data of the Belgian police do not confirm that in working-class districts, where many undocumented people live, there are more frequent violations of the law. The highest number of common thefts per capita is recorded in the neighbouring municipality of Saint-Gilles.

Many sans-papiers who cannot count on the help of relatives or friends become unhoused. In the Belgian social welfare system, dedicated shelters exist for foreigners who do not have residence permits, but the needs outstrip the capacity. From 2023, single men are not accepted into shelters in order to make room for women and families. However, they can count on the support of grassroots initiatives, such as the La Casa Tamam centre in Molenbeek.

The entrance to the large, concrete building is decorated with colourful, hand-cut and painted letters “La Casa Tamam”, in front there is a small pen with chickens and rabbits, which are looked after by the residents. This space has been operating as an official shelter since 2021. The place where the centre is now located used to be an abandoned tobacco factory inhabited by squatters. For the first year, La Casa Tamam operated thanks to volunteers and the originator – Fabrice Dupuy. After a few months, it was possible to raise money and hire about 20 employees – some of them with migration experience – who watch over the area, ensure compliance with the rules and the safety of all 340 residents (only adult men, mainly from sub-Saharan Africa). But La Casa Tamam is not only a shelter, but also a social welfare centre and a space for integration.

We pass the reception, a makeshift gym and enter the social room. Two people are playing ping-pong, someone is scrolling their phone while sitting on the couch, someone else is listening loudly to the instrumental version of Sound of Silence. There is also a small kitchen, from which wafts the smell of roast chicken and strong spices. The cook is Abdel (not his real name) from Mauritania. When we meet, he is celebrating his birthday. He looks thirty, although he doesn’t admit it.

“I’m turning 19. I mean, counting my Belgian age,” he says and bursts out laughing. Lowering one’s age is a popular practice among people who want to apply for protection or simply live in a European country. Unaccompanied minors generally have an easier asylum procedure and are less likely to be deported. From the other perspective, for state authorities, verifying the age of those who do not have identity documents can be a challenge.

The story of Abdel’s path to Europe is similar to that of thousands of others, only the countries change. Seventeen years ago, he boarded a flimsy dinghy together with dozens of other “dreamers”, as people on the road call themselves. For two days, together with his companions, he crossed the waters of the Atlantic Ocean until he reached Tenerife. From there, he made his way to mainland Spain, but had to leave due to the effects of the global economic crisis. Then he went to France, where two twin brothers and an uncle were already waiting for him.

“I didn’t like it there, I can’t say why. My uncle tried to stop me, he told me to stay put. I lasted a year, and then one day, when he left for work, I just ran away,” Abdel says, laughing. In Belgium, he applied for international protection three times, without success. “Mauritania is not considered a dangerous country. And I’ll be honest with you, I didn’t run away from danger, I ran away from poverty. Just like my brothers before me. Neither they nor my parents tried to stop me, they just wanted me to wait until I was a little older, but I didn’t listen to them,” he admits.

Europe turned out to be different than he had imagined. Living in Mauritania, in a small village, he had never thought of such a thing as a ghetto. It was only in Belgium, specifically in the port city of Antwerp, that he understood what it meant: sleeping on the street with a hammer under his head to defend himself against theft. Uncertainty and fear.

“I hit rock bottom, and finally found shelter in Brussels, in La Casa Tamam. I remember that a few years ago it was a very unorganized space, people did not want to take care of it, completely different than today. One of the first people I met was a Sudanese man who prepared dinners for everyone. I wanted to help him, I came to the kitchen for the next few days. That’s how I started cooking, today I work in a canteen in another part of the city where I also prepare free meals for the homeless together with a group of people. I’ve tried a lot of new dishes, but my favourite remains maafe, a traditional West African stew, you should try!” Abdel continues his story. He only sleeps in Molenbeek. He meets his friends in Uccle in the south or in Schaerbeek in the north.

“I’ve heard from many that Molenbeek is dangerous, and although nothing has ever happened to me, I prefer to avoid the streets here. I know that there are places where people deal in drugs, and I don’t have a problem with it, but it’s just not my vibe,” he says.

Perhaps this is his last year in Belgium. He has decided that if he is not legalized by the end of 2025, he will return to Mauritania. Missing his old home and life takes its toll on him.

“I understand all the arguments to stop immigration. It works the same everywhere in the world – we are afraid of those we don’t know. But you, Europeans, have to ask yourselves who will then work in health care, in restaurants. Migrants are simply needed. The only solution to live together is to meet and talk.”

According to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) from 2022, the employment rate of migrants in Belgium was over 60 percent. It is only 6 percentage points lower than that of native Belgians. There is also the grey area where undocumented people find mainly manual work. Some decide to go into drug dealing. One of the problems I hear about from another resident of La Casa Tamam is the non-recognition of university degrees, even if one comes from Burundi or the Democratic Republic of Congo – former Belgian colonies. The local system has also created conditions for maximum use of the foreigners’ workforce while limiting the possibility of full legalization of stay. This takes the form of the so-called orange card, issued until an application is considered, which is a temporary residence and work permit (with many restrictions).

Meanwhile, anti-immigrant sentiments are growing almost everywhere in the European Union. A few days before I arrived in Brussels, on 3 February, after eight months of wrangling over budget cuts and taxes, a new government was sworn in in Belgium. It is led by Bart De Wever, the leader of the right-wing New Flemish Alliance (N-VA). The government coalition is made up of five parties, from the right to the left.

The newly appointed prime minister announced that Belgium would introduce the strictest migration policy in Europe. It plans, among other things, to reduce social assistance for foreigners, including a significant reduction in the number of reception centres, and to limit the rights of immigrants. It also intends to make family reunification procedures more difficult. “To organize a more orderly and humane migration policy, it must be much stricter,” he said.

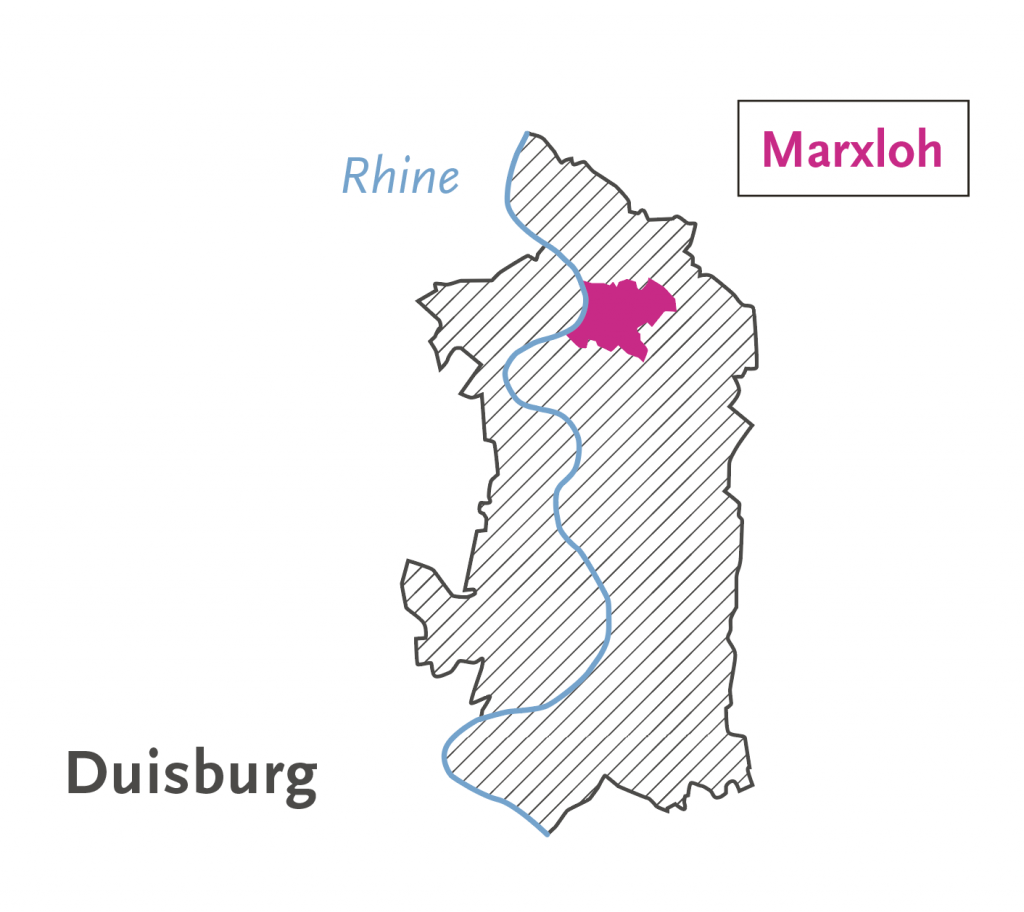

Duisburg, Marxloh

From the Brussels-South station I catch a train to Duisburg in the Ruhr area in western Germany. A few hours later, I arrive in a region that underwent an industrial revolution 150 years ago thanks to coal mining. After World War II, the Ruhr was called Germany’s “economic wonder”. Workers from all over the country came here, followed by guest workers – first from Europe (including a large number of Poles), and later from more and more distant countries. After soaring coal-based prosperity, the region was hit by a crisis related to deindustrialization in the second half of the twentieth century. This, like in Molenbeek, led to a wave of unemployment.

Among the many working-and-immigrant spaces in the region, I decided to visit the Marxloh housing estate, which is part of the Hamborn district in the northern part of Duisburg. Marxloh has received the label of a no-go zone, although in the 1970s it was mainly middle-class, and the prosperity associated with industry made the estate more prominent than downtown Duisburg.

According to various figures, between 60 and 80 percent of Marxloh’s residents have immigrant roots, and most of these do not have German citizenship. At the beginning of the new millennium, it was mainly a Turkish district, due to the dominant minority of this origin, but the situation changed after 2007, when Bulgaria and Romania became part of the European Union. Easier movement in Europe has attracted many citizens of these countries to Germany, including the Roma, the continent’s most socially, economically, and institutionally disadvantaged ethnic minority.

Duisburg, with a population of half a million, stretches along the Rhine. I get off on the south side, at the station right next to the city centre. I am greeted by a dingy shopping mall, a kebab stall, cigarette fumes, and the smell of smoked marijuana. On Saturday around noon, there is hardly anyone at the metro station. Halfway to Marxloh I change to a bus. Due to the reconstruction of the metro, replacement transport is in operation. A polite young station employee escorts me to the right stop, on the way I ask him about the infamous housing estate.

“It can be a bit dangerous, some people are afraid to go there, because, you know,” he says in a low voice, “immigrants.” However, he quickly adds that he has been there himself many times and nothing bad has ever happened to him. “It all depends on who you get. However, I wouldn’t go alone in the evenings, you never know. It is quite a special area.”

Rambling through the city for almost an hour, I pass neglected tenement houses and blocks of flats. Tasteless pastel finish, well known in Poland, is also rife here, although the whole city, especially in February, seems grey and expressionless. The impression changes when I arrive at the Marxloh shopping area – Weseler Street. As each weekend, the street is packed with families and their shopping bags containing dresses, suits, and opulent jewellery selected a moment earlier. Weseler has become the centre of Turkish-style wedding fashion. Tulle, sequins, and gold scream from the windows of surrounding stores. Forget modest elegance – there’s gotta be drip.

One of the boutiques is run by Nuray Çoban, an elegant woman around forty. We pass a future bride trying on another dress, accompanied by the admiration of her loved ones. Nuray leads me upstairs. When she turns on the light, I am struck by the glow of the white sartorial creations, among which she herself – a designer with a silk scarf on her hair and delicate make-up – looks as if she was from another world.

About 25 years ago, local entrepreneurs, mostly of Turkish origin, began to open bridal fashion stores here, filling the market gap. Nobody knows who first came up with the idea to bring the chic outfits here, removing the necessity of shopping trips to Turkey. What we do know is that over time, dresses from Weseler have also become popular outside Germany, attracting customers from Belgium and the Netherlands.

“There used to be a stationery shop here. I would buy notebooks here for school,” Nuray says, presenting the fancy embroidery. “And do you know that we have Polish women in Marxloh who married Muslims? Religion is never a problem once you get to know the other person. Conflicts arise when you don’t know people. They say it’s dangerous here, but I often close the shop late at night, go home alone, and nothing has ever happened to me. There is nothing special about this place, you can find bad people everywhere.”

A media collective launched the „Made in Marxloh” campaign in 2010 as part of the celebration of the European Capital of Culture Ruhr.2010 to counteract the stigmatisation of the estate and support the identity of its residents, especially the youth. Photo Halil Özet, Medienbunker Marxloh

From the busy Weseler street spread narrow, quiet, dirty streets surrounded by dilapidated tenement houses. I pass few people walking alone, mainly dark-skinned men. The tangle of streets leads me to one of the largest mosques in Germany. Located a bit off the beaten track, it marks its presence from afar with a 34-meter minaret sticking into the sky. The building also houses an Islamic cultural centre, a Koranic school, and a small café in front of the entrance.

The Merkez Mosque, built in the Ottoman style, was built in 2008 on the initiative of the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (DITIB), one of the main Muslim organizations in Germany, affiliated with the Turkish Ministry of Religious Affairs. The authorities of North Rhine-Westphalia and the EU also contributed financially to its construction. Fearing that such a distinctive and impressive symbol of Islam in Duisburg could cause resistance from the majority of the population, DITIB established cooperation with the city administration. During its construction alone, the mosque was visited by over 40 thousand tourists, for whom it was also an opportunity to get to know Muslims and their religion (I was also warmly welcomed and as soon as the prayer ended, I could enter and admire the inside). The mosque’s construction, which met with no opposition, was called the “miracle in Marxloh.”

It was completely different with the Central Mosque in Cologne, about an hour’s drive from Marxloh, which was also built on the initiative of DITIB. Designed by the German architect Paul Böhm, it is distinguished by high, glazed windows and a modern shape. Its size surpassed the mosque of Marxloh and became the largest in the country. Although the construction of both temples began at a similar time, in the case of the latter, groups of opponents tried to block the investment from the very beginning, which delayed the opening of the mosque by a decade. During the protests, slogans were chanted such as “We are the nation”. The demonstrators argued that the building meant consent to the “takeover of Germany” by Muslims. Others claimed that such a large mosque is a competition for the Cologne Cathedral, the symbol and most important monument of the city (incidentally, much taller than the Central Mosque). In a survey conducted at the time, only 30 percent of Cologne’s residents supported the construction of the mosque. Further protests took place in 2022, when the mayor allowed muezzins to call for prayer. Opponents demanded that the city space remain religiously neutral. In turn, the vice-president of DITIB argued that “thanks to representative mosques, [Muslims – A.M.] have become a more visible and thanks to the call to prayer a more audible part of society.”

Visibility is actually one reason why the construction of both temples was so differently received. The mosque on Marxloh is located in an already marginalized, invisible part of the city, treated more like a separate town than a district of Duisburg. Meanwhile, the mosque in Cologne, although also erected in the Turkish district, Ehrenfeld, is located close to the centre, only a dozen or so minutes’ walk from the cathedral. The transparent cooperation between DITIB, the city, and social organizations, unlike in the case of the Central Mosque, also contributed to the “miracle” in Duisburg. Rumours have arisen around the Cologne investment that it is a suspicious policy effort of the Turkish authorities.

“My husband and I were the first Turks in our neighbourhood. When we moved in, people asked what we did for a living. They were very distrustful, but that quickly changed. Good education is the basis for integration, which is why as university faculty we do not feel excluded – all our friends are native Germans. They can’t get over the fact that every Saturday I am here, in the mosque. They say: “But you’re so German, so modern!” Indeed, I am partly German, but partly Turkish. At home, I sometimes serve German cuisine, sometimes Turkish. My culture is a mixture of both and I like that fine,” she says, when suddenly a ten-year-old boy runs up to her. He treats us to Turkish sweets that he got after school. “He has the best grades in English in the whole class,” Gönül brags about her son. She wants her children to receive a good instruction in the Koran. She believes that thanks to this, they will be able to tell good from evil and will not fall into the hands of religious fundamentalists when they enter their teenage years. “There are other, smaller mosques in the area, but you never know what they preach.

Young people of mixed backgrounds often face an identity crisis, which makes them vulnerable to extremism. My mother understood this and that’s why she sent me to Christian religion classes. She believed that learning from other cultures protected against hate.

We also talk about her research. Gönül says the same thing I heard in Belgium – for people of immigrant origin, achieving success in the labour market is much more difficult, but possible, as her own experience proves. However, the non-recognition of non-European diplomas remains a problem. Although her father was employed in a bank in Turkey, in Germany he had to work in a mine. German law allows taking exams and courses to supplement the qualifications already obtained to the level required in Germany. In practice, however, the local bureaucracy is insurmountable for many foreigners.

Another problem is language. The older generations of guest workers in Duisburg do not speak German very well because it was not necessary for operating machinery and mining raw materials. Nowadays it is different, as people immigrating from Syria have to attend language classes. Compulsory integration courses, subsidized by the state, were introduced two decades ago.

“It is getting better with each generation. In the 80s and 90s, Turks and immigrants of other nationalities most often ran kebab shops. Today, their children become doctors or police officers,” the researcher points out.

Some run for political office. During my stay in Duisburg, the election campaign for the Bundestag is underway. In the centre of Marxloh, face-branded pens and leaflets are handed out by Mahmut Özdemir, a candidate from the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Born here, he represents the second generation of Turks in Duisburg.

“He is more German than many Germans,” another local politician tells me later. In his election programme for Duisburg, Özdemir declared that he would strive to ensure equal opportunities for everyone, regardless of their background, including support in finding a job and lowering rent. At the same time, he stressed that he wanted “a constitutional state in which the law is respected and crimes are nipped in the bud. Safety and cleanliness in our city must once again become a priority for all of us.”

According to police data for 2023, Marxloh is among Duisburg’s top districts in terms of violent crimes and burglaries, alongside neighbouring Hochfeld and Dellviertel, which lies close to the centre. It does not stand out much from the rest of the city, which recorded the lowest crime growth in the region in 2022–2023. Nevertheless, Duisburg is one of the many cities in Germany that are under special police surveillance, referred to as “hot spots”. Rumours and fake news circulate among Duisburgers and in the media about Marxloh and other “difficult” districts, alleging that police are afraid to enter them. Meanwhile, there is a police station in the very centre of Marxloh, and during my stay of several days – both day and night – I saw and heard police cars patrolling the area.

However, it cannot be denied that Marxloh is struggling with problems, such as the 14-percent unemployment rate and high levels of poverty, especially among children (more than half of them are raised in families receiving unemployment benefits). People of mainly Turkish, Bulgarian, and Romanian origin live side by side here, but there are also Poles and Syrians – a total of 92 nationalities.

The local flats belong mainly to the Turks, who bought them back in the times of prosperity. “The privatization of the company-owned housing stock and the lack of investment by numerous buyers, combined with declining populations, low incomes and rents, have led to further backlogs of maintenance, a spiral of devaluation, a large number of vacant properties and even completely abandoned junk properties. This had a significant impact on all areas of the Marxloh district,” reads the website of the Office for Urban Renewal and Land Management of the North Rhine-Westphalia region. Neglected, and therefore cheap, housing attracted poor immigrants from Bulgaria and Romania, hoping for a better life (a significant part of them are Roma, although the exact figures are unknown). Often, due to the lack of education or knowledge of the language, they work mainly in the informal economy, which deprives them of the right to social benefits, such as health insurance. “All this poses a serious challenge to coexistence, the cohesion of the district, and the integration of new immigrants,” the statement concludes.

Poverty goes hand in hand with social exclusion and stigmatization. The story is always the same, only the nationalities change – “Poles stealing cars” were replaced by “radical Muslims from Turkey”, and these in turn by “Roma idlers”. Gönül Aydin-Canpolat, with all her expertise in social studies, succumbed to these stereotypes herself – she explained to me that Islamophobia results from “ignorance of the other” and we all tend to generalize, only to start convincing in the same breath that the Roma’s aversion to work and inclination to theft result from their culture. “The example of the Duisburg-Marxloh district shows that new immigrants from [south-eastern – A.M.] Europe suffer discrimination from other groups in the district. The same processes are noticeable in both Marxloh and Nordstad [in Dortmund], which allows us to assume that they are common,” writes Sebastian Kurtenbach, professor of political and social sciences at the University of Münster, specializing in the issue of radicalization.

It is not only origin or ethnicity that arouse aversion, fear, or uncertainty towards certain groups. Sometimes the mere presence of “different-looking” people in public space is enough. Especially if they are groups of young, swarthy men standing in front of a shop or bar – a common sight in the streets of Marxloh.

“I live two housing estates away, but just look at what’s happening here…” says a middle-aged Polish woman who has been living in Germany for twenty-two years. We meet in front of the entrance to St. Peter’s Church, run by the Polish Catholic Mission, just a few minutes’ walk from the mosque. “This church is a bit off the beaten track and it’s quite pleasant here, but if you go deeper into the streets, there is a small ghetto, the so-called no-go zone. Police are afraid to go here because they’ve received threats. These are people who don’t want to assimilate with anyone, they would like no one to interfere with them, because you know, they have Sharia law. This is a completely different world than in Poland,” she continues. She lives in Neumühl, in the east of the city, where reception centres for migrants were opened about ten years ago. However, these were quickly closed, officially due to local misunderstandings between investors and the city authorities.

“Our Neumühl had always been clean and safe, until these centres were built. How they went out into the streets, whole gangs of them, young men, no women and children! They started picking on people, provoking fights. As residents, we appealed to the city authorities to close these shelters, because we were afraid for our safety. Almost all of us signed and we succeeded, they transferred them to other districts. Nothing ever happened to me, but they accosted me, fortunately it was always with people around. I have two daughters, aged 18 and 20, I was afraid to let them walk the dog at the time. And at the same time, you can’t say anything, you can’t show on the Internet how aggressive they are, because you get banned right away. This is all political correctness,” she concludes, warning that in Poland “we’re in for the same thing”.

What do the authorities of Duisburg say about all this? I make an appointment with Ulrike Färber, deputy manager of the Municipal Integration Centre, and Claus Lindner, member of the Council of Hamborn, a district of Duisburg that includes Marxloh. Lindner is also a local representative of the SPD.

They both take me on a tour of the housing district. We pass extremely dilapidated, grey blocks of flats, and a minute later we come out onto a street surrounded by small, brick villas, with Mercedes parked in front.

“Engineers’ families used to live here. When they moved out to the city, the houses were bought up by workers. Today, the second and third generation of immigrants as well as native Germans live here. As you can see, unlike the other streets of Marxloh, there is no rubbish here, because people who have lived in the district for years know what the rules are. In other areas, 2,000 people leave every year and the same number move in. The new ones need time to learn how to be good neighbours. In addition, for large families, the bins are simply too small, so rubbish piles up. I know a lot about it, because waste management is part of my job,” he explains.

Just in front of the villas there is a large park and a playground where two children play. This is an element of revitalization and greening of post-industrial areas. We also pass still working factories, the mosque, and Weseler Street. My guides keep emphasizing that they want to show how diverse Marxloh is. Claus greets someone he knows every now and then. He has lived here almost all his life, and one of the main goals of his political career is to change the image of Marxloh.

“When deindustrialization began, I was still a teenager. I remember that people who had previously worked in the same factory suddenly began to notice the differences between themselves. A German would say, ‘If some Turk gets my job, I’ll beat him!’ The whole estate suddenly became different,” he recalls.

We walk down the street, Claus stops in front of one of the buildings and points to a notice hanging on the door.

“This building has been closed due to disrepair and the danger of collapsing. We have a special municipal unit that deals with renovation, but it cannot do much, because the owners are often abroad and it is almost impossible to reach them. The Bundestag could take up the matter, but in Berlin no one cares about our problems.”

German federal authorities run a number of social programmes aimed at disadvantaged areas, including working-class and immigrant districts – from education, through housing, to fighting extremism and supporting civil society. Despite this, Germany, the third largest economy in the world, is facing poverty that has been growing for two decades, affecting more than 14 percent of the population, or 12 million people (Human Rights Watch data for 2024). “An increasing number of people do not have the financial resources to afford essentials such as food that ensure a healthy diet and struggle to heat their homes, far less pay out of pocket for necessary healthcare expenses. A central reason is a major restructuring of social security that began in 2005, and the related growth of a low-wage sector,” we read in the HRW report.

In 2015, Marxloh was visited by Angela Merkel, the then German chancellor. This was part of the Gut Leben in Deutschland (Good Life in Germany) programme, under which the authorities carried out a series of public consultations throughout the country, including in the most disadvantaged cities and districts. The aim of the programme was to improve the general quality of life of the country’s inhabitants and to gauge the public mood, especially since more than a million people had come to Germany at that time, mainly due to the war in Syria. However, I do not hear that Merkel’s visit significantly changed Marxloh’s situation.

I ask Ulrike Färber about the city’s efforts to integrate the district. She points to the creation of opportunities for different cultures and social groups to meet, for example through sport – thanks to EU funds, Marxloh has created pitches where professional training sessions are regularly held for youth football teams. The City Council also supports the activities of organizations such as Tausche Bildung für Wohnen (Education for Housing), which helps children learn from teachers and volunteers. Schoolroom shortage is one of the biggest problems in Germany – opposite the headquarters of the organization stands a long, tin prefab building, which turns out to be an additional, hastily built school.

“There was a moment when there were too few children in the country and many schools were closed. In 2015, many families suddenly came to Germany and it turned out that there was nowhere to accommodate the new students. I know that the authorities are doing what they can to solve this problem, but it takes a very long time to build schools and obtain all permits,” Färber points out.

Ulrike and Claus are focused on finding the most effective ways to counteract conflicts arising from misunderstanding the Other and helping new arrivals to stand on their own two feet and integrate into the German community. However, people like them are slowly becoming a minority.

A few days after my departure from Duisburg, on February 23, 2025, the Bundestag elections took place. The CDU/CSU bloc gained the most support with almost 30 percent. The far-right and anti-immigrant party AfD (Alternative for Germany) saw a huge increase, winning more than 20 percent of the vote, putting it in second place. The SPD came third, with 16 percent of the vote (in the Duisburg II constituency, which includes Marxloh, Mahmut Özdemir of the SPD won. He was closely followed by Sascha Lensing from the AfD).

Taking over from Olaf Scholz from the SPD, the leader of the conservative CDU, Friedrich Merz, became the new chancellor in early May. In January, he had managed to clearly show in which direction he intends to lead Germany’s migration policy. Acting jointly with the AfD, he introduced a resolution restricting the right to apply for international protection, in the aftermath of a 28-year-old knifeman from Afghanistan fatally wounding two people in the Bavarian city of Aschaffenburg. The bill was ultimately voted down by the opposition, which called it inhumane and illegal. Meanwhile, there are more and more voices hostile to the presence of immigrants in society. A poll by ZDF’s Politbarometer shows that 56 percent of respondents support permanent border controls, and 63 percent support barring entry from people without valid documents.

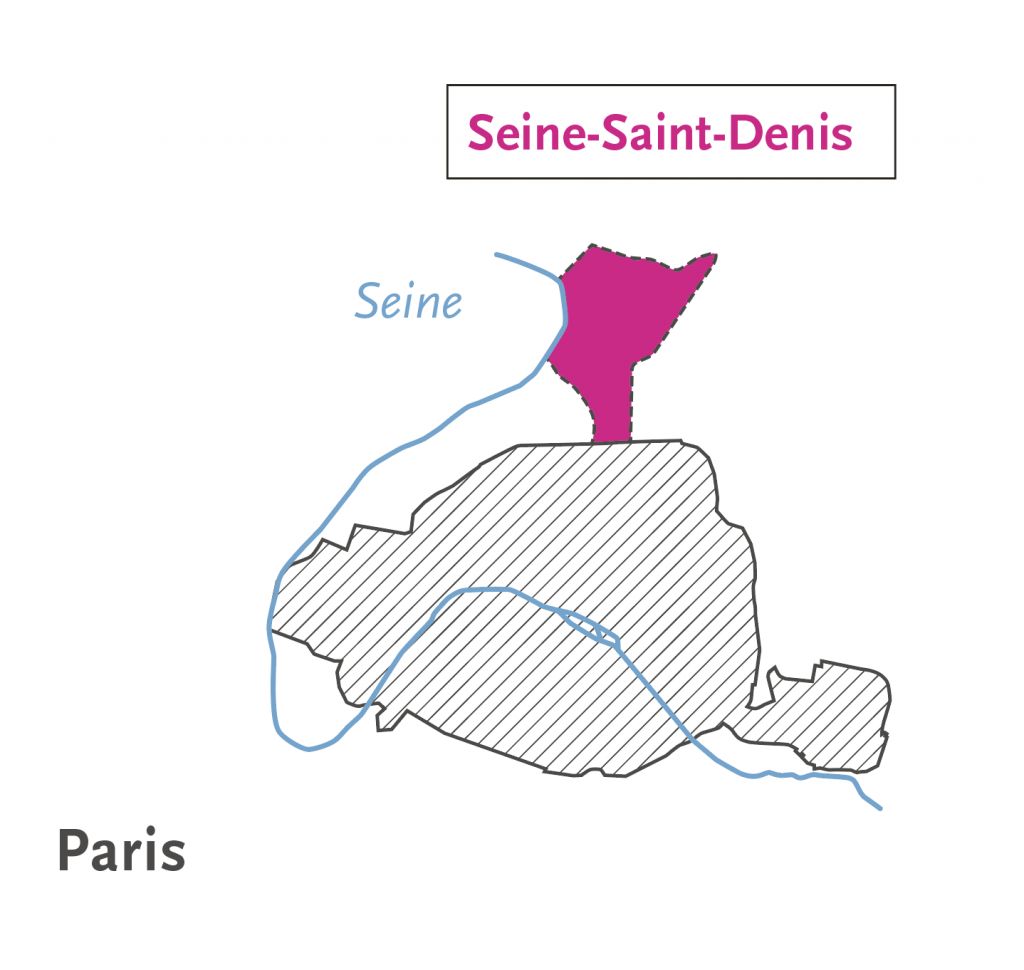

Paris, Seine-Saint-Denis

The last stop on my route is Paris, or rather a department near Paris called Seine-Saint-Denis, or Department 93. It is just one stop from the French capital by suburban railway. The surroundings of the North Railway Station (French: Gare du Nord) are as Parisian as you can imagine – well-kept tenement houses in shades of sand, boutiques, and cafés. A little further north, French architecture gives way to low blocks of flats holding on to existence against encroaching glass office buildings.

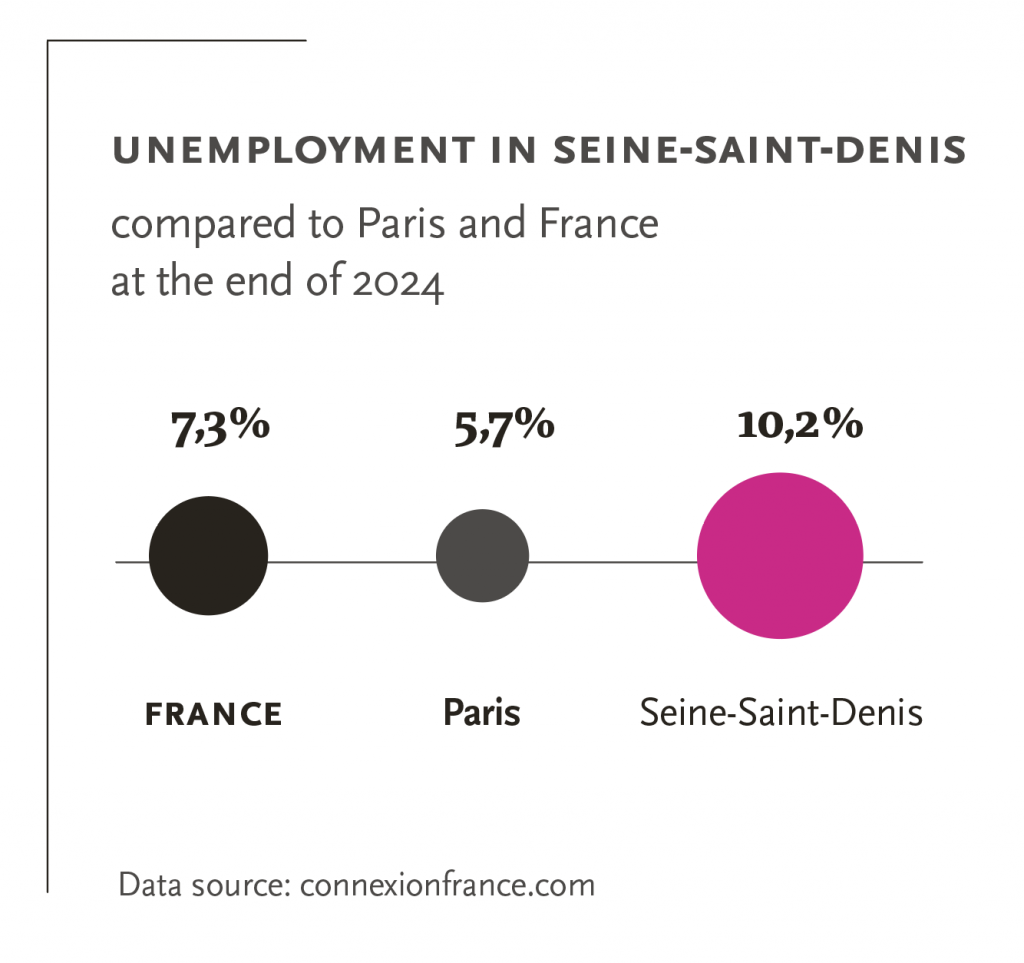

I arrive in Saint-Denis, one of the 40 communes that make up the Ninety-three – considered one of the most dangerous departments of mainland France. Interestingly, there are fewer crimes committed here than in Paris itself. Despite this, places such as this one – called banlieues, or suburbs, or rather workers’ high-rise housing estates surrounding large metropolises – most often evoke negative associations.

This is a story that we already know: in the 19th and 20th centuries, industry developed dynamically in the department, which attracted immigrant workers, mainly citizens of the former French colonies – Algerians and Tunisians. The situation began to deteriorate from the 70s of the twentieth century onward, when factories were gradually closed in favour of imports from countries where production was cheaper. The department has a population of about 1.6 million people, with as many as 39 percent of families living in social housing. About 30 percent of the inhabitants of Seine-Saint-Denis are people with migration experience.

The plight of Department 93 cannot be understood by focusing on economic factors alone. For example, why here, among other places, did the famous protests of 2005 erupt, images from which – burning cars and broken shop windows – reached the international media? Perhaps the most accurate answer is given by the title of Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 film, which takes place in this department – Hatred. The picture tells a story of violence between the police and citizens (mainly of immigrant roots), which, despite the passage of time, remains a burning problem in France.

On the border of the communes of Saint-Denis and Aubervilliers is a canal which I now follow towards the Stade de France, the main arena for the 2024 Olympic Games. The walls around the canal are covered with graffiti and murals, among which one particularly catches my attention – it commemorates the Paris massacre of 1961. This was the name given to the bloody suppression of peaceful demonstrations organized by Algerians demanding the independence of their country. It is estimated that, as a result of police action, upwards from several dozen to as many as two hundred demonstrators were killed. Algeria freed itself from French rule a year after these events. However, the memory of colonial times and the several-year-long war for independence is still alive and affects the French society of today.

“The Algerians are furious. They come here because they want to take back what belongs to them, all the stolen prosperity on which this country was built,” argues Marloy, rolling a joint. Originally from Guyana, he has been living in the Ninety-three for many years. We are sitting in a square right next to Saint-Denis station. Marloy wears long, grey dreadlocks and a baseball cap with a French flag that peeks out from under an olive Rasta cap. He is one of those people who has a ready answer to everything. He speaks erratically, but I manage to catch his main thought: if you are an immigrant and you want to work here, you can manage, but you have to be aware of the human rights you are entitled to, otherwise you will not achieve anything. His friend Kevin, a house painter from Ghana, agrees:

“Especially if you want to legalize yourself here. If you don’t have a family in France, the easiest way is to find a French wife,” he says.

It is true that the French authorities have one of the strictest migration policies in the European Union – France is the leader in the number of deportations, and for years, despite the needs, has not increased the pool of places in intake centres.

According to human rights activists, this is a way in which the authorities hope to discourage people from immigrating from the countries of the global South. In reality, however, tens of thousands of people arrive in the country informally every year in search of work or simple safety.

The vast majority of them end up on the street. Until a few years ago, along the canal, by the wall decorated with a mural commemorating the events of 1961, there was a tent city created by unhoused people. Today there is no trace of it.

“They’ve evicted the hell out of them, some moved somewhere further away, some have gone back to their home countries,” Marloy says, taking a drag of the joint. This is confirmed by the accounts of non-governmental organizations associated in the collective Le Revers de la médaille (French: The Other Side of the Coin/Medal), which defended the rights of migrants and the unhoused as preparations for the Olympics were being enforced. It published a report proving that from April 2023 to May 2024 hundreds of such people were forcibly resettled and squats were torn down so as not to spoil the image of France, as the Games were supposed to project a sense of equality and freedom. Unfortunately, many of those individuals lived in the vicinity of the stadium in Seine-Saint-Denis – where a significant part of the Olympic infrastructure was located.

The whole endeavour testifies to sweeping the social problems that France is facing under the rug. I learn more about this from the spokesman of the collective and street-worker Paul Alauzy:

“We had observed this brutal policy towards unhoused people long before the Olympics, but in 2023 the scale of the ‘purges’, as we call them, has tripled,” he relates. What happened to the people removed from the streets? According to the information gathered by the collective, they ended up in shelters far beyond view of the Games for several weeks. “Among them were also sex workers, drug addicts, Roma. After the Olympics, most of them had to leave the shelters and were back to square one. Don’t get me wrong, we don’t want people to live in tents, but pushing them out of Paris for a short time is no solution. This only cuts them off from the community they have built here,” he argues.

Although the authorities are striving to increase the number of places in shelters, they still do not meet the real demand, rejecting hundreds of applications for admission, including families with children and pregnant women. According to official data, about 350,000 people live unhoused throughout the country. However, Paul believes that this is a huge underestimate, and their number is constantly growing. Many of them are people applying for international protection who have nowhere to go during this long procedure. Others are waiting for legalization based on their many years of residence, and in the interim rely near exclusively on illegal work for survival. Patience may pay off in the end, but living on the streets comes at a high price.

“We work with psychologists who are convinced that the violence and hatred experienced by people who are unhoused leads them to aggression and the ability to commit crimes and carry out attacks. Even if it is a minority, we are dealing with a serious problem. I remember speaking with a man just after the knife attack in Lyon took place [on August 31, 2019, a 33-year-old Afghan man attacked passers-by with a knife at a bus stop; eight people were injured, one died. The psychiatric assessment showed that the man was in a state of psychosis at the time of the attack; No links with terrorism have been shown – editor’s note]. He told me then:

‘If I continue to live on the streets, in two years I will be like him. I never thought I could hurt anyone, but after I was assaulted and the police sprayed me with gas instead of helping me, I’m starting to freak out. It’s been years, and I just want to finally be able to work legally. How much can a man endure?’”

Moments later, Paul shows me photos of the canal just before the Olympics. In place of a tent city resembling a Tetris puzzle, concrete blocks appeared to prevent the tents from being set up again. Today, there is no trace of either. Few returned to the water – today I see maybe two or three huts. I recall a moment in the coverage of the Olympics, when rapper Snoop Dogg was dancing along the same road, carrying the Olympic torch among a crowd screaming with excitement.

According to some, the Olympics and the huge funds dumped into them are a wasted opportunity for the development of Department 93. One controversial project is the Olympic Village, which was erected in the commune of Saint-Ouen, directly bordering Paris. Modern, spacious glass buildings of the Olympic Village now stand empty. On the one hand, giving this space to residents seems to be a good move. After all, it would be a relief to local infrastructure, a huge investment in a poor commune. On the other hand, as Alauzy convinces me, the prices of apartments in the village are significantly higher than the average apartment in Saint-Ouen. “This is the greatest hypocrisy of the Games: everyone benefited from them, except for the least privileged,” he concludes. In his opinion, the village will be inhabited by wealthy people moving here from Paris. It will be another instance of gentrification, which the municipality has been experiencing for a long time.

In Saint-Ouen, a grassroots organization called 93 OAK has been supporting young people from poor and excluded neighbourhoods through student exchanges between Seine-Saint-Denis and Oakland, USA. Its headquarters is located in a complex of buildings taken over from the city, where numerous social initiatives are undertaken. Here I meet 21-year-old Mariam, a film student at a school run by the Nouvelles Écritures association, a black Muslim.

“Do you know Spike Lee?” she asks me. “He’s a director from Brooklyn, one of the greatest African-American filmmakers. I want to make films like his. He always puts his culture and origin front and centre. I want to finally see our community on the screen. Do it for us. You know, my favourite subject in movies is black women. In France, they are always shown in two contexts – sexualized or gang-related. A black woman in French cinema is poor and uneducated, she cannot speak about herself and for herself. And I want to see women as I know them. As I am.

I remember that director’s film She’s Gotta Have It from the 80s. Nola, the main character, has an affair with three lovers, and each of them wants her only for himself. The message of the film is clear – her body, herself, belongs only to her. Mariam likes this movie.

“They say that we live in a jungle, that 93 is a jungle. Journalists, politicians, people from Paris tell us how we should live, but they come from a completely different environment. They can’t know what it means to grow up feeling like you’re not able to achieve social advancement.”

“We live in completely different worlds – I remember times when we didn’t even have food. Those who are supposed to represent us are not us,” she continues.

Mariam refers to herself in the plural because the sense of community in department 93, especially in her hometown of Saint-Ouen, is very important to her. When a boy from her block of flats was killed in a street shooting, all the neighbours mourned him alongside his family. “When one of us dies, I feel as if I had died myself. I know it could have been me.”

Although the full number of homicides in the Ninety-three is not widely known, the one related to feuds between drug gangs has grown from four victims in 2023 to 15 a year later. There were many more attempted killings related to drug trafficking – 73 so far in 2025. In addition, the department has the highest rate of domestic violence in the region, with victims predominantly female.

“Being a black woman may not be easier than being a black man, but it’s a different kind of struggle. Perhaps my brother will never understand me and I will never understand him. I don’t know what it means to live in constant fear of police aggression. I don’t know what it’s like to be afraid of people who should be protecting you,” the girl admits.

Mariam’s father was born in Senegal. There he met her mother, a French citizen, and there they got married, later settling in Saint-Ouen, where their children were born. They were married for ten years, after which the father, now divorced, returned to his homeland.

“It’s a bit of a difficult topic, because in our community we don’t talk about love or sensitivity,” Mariam says, laughing. “My situation and that of my siblings is privileged because our mother comes from here. Many of my friends have both parents who were born in another country, which means that they have a communication barrier and their relationship suffers. For example, love – they understand and express it differently. On top of that, we all ask ourselves where we belong and who we are. Do we even have a home?”

I also talk to Mariam about racism and Islamophobia. She experiences both, although this was not always the case. Most of her peers in the diaspora grew up together and rarely left the department. They had their shops, their places, their school. Nothing changed until they grew up and wanted to explore a bigger world.

“The majority needs us to do specific jobs, such as cleaning or nursing. They need us, but we have to know our place. Problems start when we want to achieve something more,” says Mariam.

According to the 2021 report of the Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons, in France more than 40 percent of people with migration experience find employment one year after obtaining official status, but these jobs represent professional demotion. They are primarily employed in the hotel, catering, and construction industries. Over 20 percent remain unemployed. Another problem is the glass ceiling, which is difficult to break through for people like Mariam. According to a 2023 survey conducted by the authorities of the Seine-Saint-Denis department, almost half of the residents believe that they have experienced discrimination in the labour market. As many as 37 percent of respondents admit that they have been victims of territorial discrimination, i.e. discrimination based on their place of residence. As many as 43 percent of respondents experience racial discrimination. Unequal treatment is also felt by the vast majority of women. The survey also shows that these phenomena are growing stronger every year. Reading this report, I remembered a conversation with a Bangladeshi salesman in a local store in Aubervilliers: “The French are not the problem, they are not racists. Blacks, Asians are okay, the problem are the Arabs, because they steal,” he said.

My thoughts go back to the couch in 93 OAK. Mariam said to me, “In 1993, I’d never experienced racism and wondered what that was about. After all, people were saying that France was racist. I thought it was a lie. It wasn’t until I grew up that I realized that I hadn’t experienced it because I was the good black, I’d stayed in my place. When I finally wanted to go beyond – intellectually and physically – I started going to Paris to clean and cook. I understood then that my France is not their France. For the first time, I felt what racism is.”

“What does that mean?” I ask.

“Often you just see it in the look. Then you notice that you are spoken to differently, and finally, treated differently. I’ve had a security guard follow me around a store. When I went out without buying anything, I felt like I should apologize, convince him that I hadn’t stolen anything. After all, we are all the black woman he saw on the screen. You know, I don’t want to be like that guy. I’m more interested in love and empathy. I don’t want to treat those people the way they treat us. I believe that no one is born racist, everything is a matter of education. People are complicated – we can try, but we will never fully understand another person.”

“It’s very telling: I can’t be an educated woman wearing a hijab. When, as a college student, I sat down in class in a hijab for the first time, it was a breakthrough for me. I could be a Muslim and a student at the same time. It was the most beautiful thing in my life.”

“It gets on my nerves that feminists tell us what we should be like as women. They do not try to understand us, they try to convince us that our culture puts women lower than men. Tell me, how can you call yourself a feminist if you don’t allow yourself to think that women from a different culture can think differently?” she asks.

the community of her Muslim brothers and sisters. This unity, in her opinion, is being split by two things: the media and terrorists. She well remembers the events of November 13, 2015, although she was only 11 years old. She had never been so scared in her life as when members of the Islamic State carried out one of the bloodiest terrorist attacks near the Stade de France, killing 131 people and injuring 350. The attackers were Belgians and Frenchmen of Arab origin, all second-generation immigrants.

“I didn’t understand why they did it. They spoke about Islam in a way that I didn’t comprehend and didn’t want to. From the media, in turn, I learned that it was I, a Muslim, who carried out these attacks. That I am equally responsible. Both of them scared me. They also made me afraid of Arabs, my ummah. It stayed with me for a long time. However, I do not think that terrorism results from poverty or stigmatization, it is rather the fault of bad guides who can mess up your thinking regardless of what social class you’re from,” she concludes.

“Many of those who went to take part in jihad were young people. They imagined it would be an adventure, almost a computer game. ISIS knew well how to sell to them. It is easy to tell a mythologized version of Arab culture and Islam to generations who were born already in Europe. You can pick and choose just the attractive bits,” says Przemysław Wielgosz and adds that both in the 19th century and today, the discourse on working-class districts has the same goal – to deprive the people living there of their voice and political subjectivity. “That is why the term no-go zone is so useful, because if someone lives in a zone dominated by crime, it is difficult to treat him as a partner in a discussion – after all, he is a potential criminal,” notes the publicist.

Wael, like Mariam, never recognized his neighbourhood when watching the news of the riots in Department 93. He decided to tell the story of this place himself. This is how his documentary project was born, which over time included banlieues from outside France.

We meet in Aubervilliers, in the cozy Auberkitchen restaurant run by his friend Yann (of Algerian-French origin). You can try Tunisian, Indian, or French cuisine here. There are also concerts and film lectures. Auberkitchen is above all a meeting space and one of many grassroots artistic initiatives in the Ninety-three. The inhabitants are changing the image and landscape of department Seine-Saint-Denis in multiple ways. On the way to the restaurant, I pass several community gardens, in some of them groups of people have already started to prepare the ground for the coming spring.

“My father was obsessed that I should go up in the world. He pushed me towards achievement despite my scarce cultural capital. He always told me that we had to work twice as hard as white people to prove our worth,” Wael says. He lives in Pantina, right next to Aubervilliers. His father came here from Tunisia in the 1970s and worked as a French teacher in a public school. His mother is a native Frenchwoman. “From when I was a kid, I remember birds singing at the canal. We lived in a working-class district, together with immigrants from Yugoslavia or Turkey. But there were also wealthy people from the upper social classes. Today, it is much more difficult for immigrants to earn money, there is unemployment and a housing shortage.”

Wael, like Mariam, feels privileged because of his mixed background. The price for this is a constant sense of alienation.

“Every time I introduce myself to white French people, I hear: ‘Where are you from?’ I say that I’m from here, and then they ask: ‘But where are you really from?’” he says. He always changes his Arabic name and his address to something else in his CV, or it is difficult to rent an apartment or find a job. And he has worked practically everywhere – in a kebab bar, in the sales department of a company, in an NGO. Today, he is a full-time documentary director.

“I chose this path to remember who I am, where I come from, and to be proud of it. I’m not going anywhere. The banlieue is my home,” he concludes.