Beyond these hills lies Syria. And here, in a tent of white plastic and beams, is the women’s centre. All around, there are 340 other tents, each housing at least four people. You can hear the crowing of a rooster and a muezzin’s call. There is no school, no doctor, no international organizations. Just a heap of worries: how to pay, what to use for fuel, what to put in the pot, whom to aid.

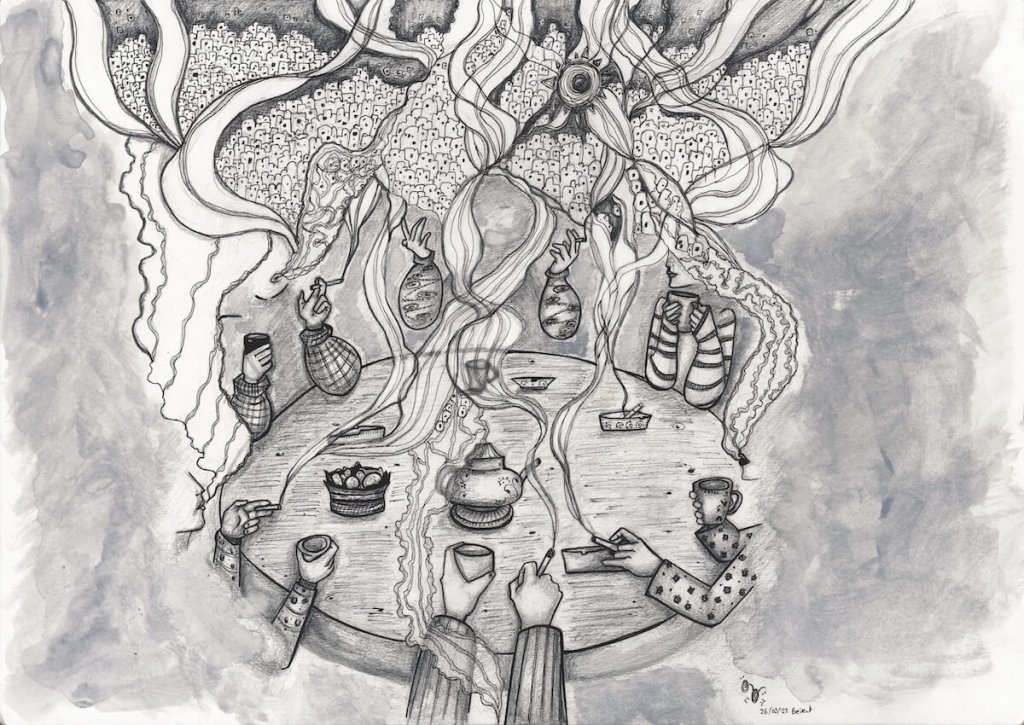

But recently, there is also this place, run by six women: a widow, a housewife, a neighbour from nearby tent, unemployed women; four Syrian, two Lebanese. They called it Together for Justice.

Fatima is responsible for finances, Ragda, who is the only one living in the camp – for communication, Mayada – for logistics, and Naima and Ghazal teach reading and writing. Nisrin is the leader. “But it’s rotational leadership, so we switch in that role,” they explain. They speak over each other, loudly – an energetic female tornado.

“Cigarette?” asks Fatima, because sharing smokes is a hospitality ritual, same as a communal meal and coffee.

Today, we witness a reading and writing lesson. But on another day, there might have been a session about violence, child marriage, or women’s rights. There are so many applicants that most go on a waiting list.

“We have a hunger for knowledge,” says Ragda of Raqqa, Syria, a tiny woman in her thirties, wearing a floral scarf on her head and a furrow down her brow, a mark of constant worry (how to pay, where to get, what to cook with). “The camp is a bad place. It leaves a mark on everyone, especially children. I managed to get out of here for a time, complete a course, do something for myself. Now, I want the same for other women.

The ambivalent aftermath of the Syrian revolution

Saura. The camp lies in the Bekaa Valley. The Bekaa Valley – in eastern Lebanon – stretches along the border with Syria and Israel. “Fertile”, “agricultural heartland” – these are its descriptions on the web. The first thing you see here, however, is mostly concrete. An endless line of towns, urbanization without rhyme or reason, fumes – because the highway to Damascus runs right between the buildings. A grey-and-brown purgatory with no hope of rest for the eyes.

What catches the eye is the fist. It stands by the roadside, about five meters high. It is white with a black border and an inscription: saura – revolution. There are such fists in many places in Lebanon, including the capital, Beirut. They commemorate the anti-government protests that swept the country in 2019, rousing millions. The prime minister appointed as a result turned out to be even worse than the previous one, corruption is as bad as ever, the economic crisis has deepened. Everything was to change, nothing did.

It was the same with the protests against Bashar al-Assad in neighbouring Syria in 2011, the coup in Egypt, the demonstrations in Iraq. Failed revolutions.

Defeats? Not necessarily, says French anthropologist Charlotte Al-Khalili. They failed to make changes at the top, true. But it is time to rethink the paradigm shaped by the Enlightenment in the West, that revolution is a sharp political cut, a sundering of a “before” and an “after.” “[D]espite its apparent defeat in political terms at the national level, the Syrian revolution […] led to profound social changes that are experienced in the present and understood as irreversible,” writes Al-Khalili in Rethinking the concept of revolution through the Syrian experience, an article for the website Al-Jumhuriya.

From this perspective, the revolutionary fist in the Bekaa Valley is quite appropriate. About 400,000 Syrian refugees live here. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), three quarters of the Syrian arrivals in Lebanon are women and children (2018 figures). One Lebanese activist once called the Bekaa Valley “the Syrian empire of women.” An overstatement, since life here is extremely difficult. But their way of living does challenge the images that come to mind when one reads: refugees, Syria, Muslim women, camps.

So, to put it in images and captions: Lebanon: a state on the brink of economic and political collapse. Inflation above two hundred percent, three-quarters of the population suffering from poverty, thirteen months without a government in 2020-2021. Syrian refugees: a crisis within a crisis. One and a half million, most in the world per capita. Camps. Humanitarian organizations. Victims of war and patriarchy.

Care and sisterhood. The beginning of a new revolution

Ola Al-Jundi’s apartment is pretty and warm. When we enter, a winter ritual is in progress: the unfolding of the carpet. A young woman, some children. I do not ask who they are, but I guess this is about care: someone is supporting someone, someone has taken someone under their roof. We have to wait a moment, because important decisions are being made. The new blue carpet – this way? Or maybe that?

We wait. “We” – because there is no point dominating a text about sisterhood with a fictional “I”. Each conversation involves the three of us: Inga Hajdarowicz, a sociologist who has been researching feminist methods of working with refugees in Lebanon for five years; Wissam Tayar, an interpreter; and I, a reporter. We sit in the kitchen, around a table. On it, some cigarettes and a large box of tissues.

“I have always been quick to tears, but recently I wear my emotions on my sleeve even more,” says Ola. Mother of the Revolution was the title of an article about her (on the Heinrich Böll Foundation website). In the accompanying illustration, a giant Ola is looking down with a smile at tiny figures entering a school. In reality, she seems much more fragile, less majestic: a medium-height woman, about fifty, her hair a shade of burgundy.

What is magnificent is her biography. Ola – a daughter of Syrian communists, Ola – a maths teacher from As-Salamiya, a city of 67,000 (which has existed at least since 3,500 BCE), Ola – who would tell students: “The schools are ours.” Ola – one of the leaders of the revolution of 2011, twice arrested and tortured, Ola – the founder of the democratic school in the heart of the Bekaa Valley, and finally, Ola – the driving force behind the leadership course for women (more on that shortly). There are many possible ways to tell the story of Ola Al-Jundi. Let us pick the revolutionary one.

Once, in Syria, one of her students told her that his schoolmates were preparing an uprising. “It’s not the time yet,” she told them. “When it comes, I’ll be there before you.”

And she was, like thousands of other women. The forgotten participants of the forgotten revolution.

“There were so many girls involved,” another Ola had told us the day before, a student who took an active part in the protests. “Demonstrating, organizing. Most also had to fight at home, for the chance to get involved. And then, they disappeared. They were not there when decisions were made, they are missing from stories and from collective memory.”

Ola Al-Jundi was one of the few women in As-Salamiya to work on a local coordination committee, the likes of which were set up across the country to organize the demonstrations. Among other things, she handled recruitment. Her function was a crucial one. But in order for the great machine of protest to work, thousands of micro-involvements were needed.

“We organized joint childcare, including for those displaced, to take part in the protests,” Ola says, taking a draught of a cigarette. “The women called men and invited them to lunches – it was a code, of course, it was about demonstrations. There, we acted as a kind of protection. When young boys were being detained or beaten, women threw themselves at soldiers or agents: ‘Leave my son alone!’”

It was a change at every level: generational, political, social. But not only. “During the revolution, I was born again as a mother,” says Ola.

Her daughter, then a teenager, once asked if she could go with her to a protest. “If someone wants to go to a demonstration, they shouldn’t ask for their parents’ permission,” she said. Her son went out on the street with other students from his school.

“I was terrified for them,” Ola says, “but I couldn’t forbid them from doing this.”

Next, Ola adds something that can be considered the definition of the politics of care. “The fact that I am a mother began to radiate to other relationships I had with people during the revolution,” she explains. “I thought, ‘If we manage to build trust-based relationships at home, why not do it on a larger scale?’”

Agency. A leadership course for women

Samar Yazbek, a Syrian writer and journalist, came to the same conclusion in a book about her participation in the Syrian revolution, A Woman in the Crossfire. In 2012, the book earned her the PEN/Pinter Prize International writer of courage award, which Yazbek – then a refugee in France – used to create an organization supporting women in Syria. It was supposed to be a network of centres – safe spaces where they could learn skills, discuss, and get an education.

“The idea was to do politics at the heart of violence,” is Samar Yazbek’s poetic statement of purpose in a video on the website of the Women Now for Development initiative thus created. The idea was also that the future democratic Syria should never again dismiss the voice of half its population. To let leaders emerge who, as utopian as it sounds today, other women would be able to vote for.

As Assad’s noose tightened, the women’s centres began to migrate along with their users: to Turkey, to Lebanon. It was in Lebanon that the women’s leadership course was launched a few years ago.

Feminism. Change begins at the grass roots

The course’s aim is simple: it is about empowering and training future local community leaders. Not that Lebanon lacks non-governmental organizations directing their programs to Syrian women refugees. On the contrary: it is easy to get a grant for “gender stuff”. Except that this is not about another offer of an external NGO for local beneficiaries. There are Syrian women refugees on the one side and on the other. In fact, there are no sides. There is a community of shared experiences, a common cause, a horizontal relationship, and learning from each other.

Participants of the course spend one year (formerly two years) talking about women’s rights, gender, violence, LGBT+, political systems, participation. Women from the camps, mothers of seven children, widows, students, fugitives from massacres, unemployed engineers. And then, under the guidance of mentors, they create their own initiatives, projects, micro-contributions towards change at the most local level.

Ola anticipates my question, saying that if I had asked her – even in 2013 or 2014 – if she was doing feminism, she would say that she was more concerned about social and economic rights. “In Syria, feminism seemed elitist to me,” she says. “I knew the names of the activists, but I didn’t feel that their work had anything to do with my life.”

In Lebanon, the situation changed. “We were uprooted from our land. Very different people began to gravitate towards each other, when in Syria they would have probably never met,” she explains.

Her path crossed with the paths of those activists whom she had known only by reputation. She started reading about feminism, discussing it with her daughter. Before that, during the revolution, she thought that she was one of the few women in decision-making circles because others had no such competences. Later, she understood: if they do not have competences, they must be given them. The “elitist” Feminism, in turn, absorbed the lesson that every change begins with working from the ground up.

“What is the most important thing in all this?” asks Ola, lighting another cigarette, and answers herself: “Points of reference.” The course’s participants meet people who are like them, who fight the same battles, and they had managed to achieve something. Thanks to them, they discover that they do not have to be “someone” to contribute to change, that their experience and knowledge are also important. And that acting in one’s immediate environment is also politics.

The course’s participants meet people who are like them, who fight the same battles, and they had managed to achieve something. Thanks to them, they discover that they do not have to be “someone” to contribute to change, that their experience and knowledge are also important.

She, too, she says, was an “ordinary person,” and her husband was a “nobody.” All they had were vision, dreams, and determination. Today, their creation, Gharsah, a Syrian children’s school in the Bekaa Valley and a support centre for their mothers, is one of the best educational institutions in the area. This is what schools in a free Syria might have looked like. In a video on their Facebook page, the children and Ola discuss the choice of a new teacher and the reasons they are not happy with the candidates on offer. The discussion ends with the children chanting: “The people want Mrs. Samah, the people want Mrs. Samah!”

It sounds right, everything makes sense in this warm, cosy kitchen in the middle of the Bekaa Valley. But the day before, in Beirut, I heard someone say: in Syria, people just lived their lives, and now they have fallen into the clutches of the NGOs and they go on about “gender”, “participation”, “leadership”. What for? Does this change anything?

“I used to think big politics was the most important thing, too,” Ola replies. “I even went to a conference in Geneva. But I quickly realized that these meetings did not do anything for the people of Syria.”

She came to the conclusion that it was better to focus on laying the foundation, because without it no change would be possible. And change comes when – as she says – you are able to understand what is happening and accurately name it. When you see where you are as a woman and what is wrong. The connection between the personal and the political then becomes so tangible that it cannot be ignored. She felt it very clearly during the revolution, she drew strength from it.

“When you see it, you can’t keep quiet,” Ola concludes, and I think of the words of a certain black woman born in Harlem, with whom she would probably find a lot to talk about. “As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring of ideas,” wrote the poet and activist Audre Lorde in her book Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches.

When we leave the kitchen, the blue carpet is already unfurled. It is placed differently than before, across the room. So, we lean over it, standing in a circle again, together. “Yes, this will be best,” the women’s committee decides.

Resistance and self-organization. Daily survival strategies

Resistance and self-organization are actually a necessity. In the Lebanese state, where a civil war of all against all was raging until 1990, a great many things are simply unavailable.

There is no free, public health service, no public transport. State education is floundering. Access to everything vital is determined by wasta, meaning your “clout”, or “connections”. The crisis has caused electricity outages and a shortage of fuel.

Lastly, there are no official refugee camps, only private camps where you have to pay the landowner to live under a tarp. It is a long story that, in short, goes like this: in 1948, the tiny Lebanon welcomed – as it turned out, indefinitely – 100,000 Palestinians, and then tried to protect itself from other “guests”. Because that is what Syrian men and women are by law: guests, to whom the Lebanese state has temporarily lent its territory and towards whom it has no obligations.

As a result, the campgrounds are scattered along the Bekaa Valley in a rather chaotic way. This one, for example, is located practically in the middle of the town, among the houses. Untypically, it only has nine tents.

In one of them live Jurie, her parents, her brother, and his wife and child. It has wooden walls, a TV hanging on one of them, a mazut stove, a masonry wall base. It is actually more of a barrack than a tent.

But there is not even a millimetre of privacy, so we are talking somewhere else.

Jurie is wearing a beautiful, silver-embroidered kerchief on her head, but she is beaming for another reason. She has just enrolled in college, finally the programme she dreamed of (political science). Today, she also managed to renew her right of residence, which is an even greater achievement.

If the story of Jurie was meant for a non-governmental organization, it would be one of success and overcoming barriers (success is needed to convince donors).

If it were a “humanitarian” story, it would focus on suffering.

But the true story of Jurie is this:

There were three sisters, Jurie, Suri, and Hurie. They lived in a village without a municipal office or a clinic, where the one public service was garbage collection.

Jurie, her sister, and her cousin were the only girls in the village who had graduated high school and then went to college. Parents set them up as role models for other girls.

Jurie and her sister could study because their father supported them. He had not finished school himself, but in the village, they called him “the professor”. Jurie was studying to be a translator, because this department was the closest. However, she did not enjoy her student ID card for long because, as her first year was ending, war reached their area. Her mother and siblings went to Lebanon. Her father stayed with her because she had an exam in September.

But so what, if she could not get there. One road to Aleppo was controlled by Assad’s forces, the other by rebels, including ISIS. And then the university buildings were bombed and that was it for college.

In Lebanon, Jurie, Suri, and Hurie found jobs in a diaper factory. They got a workers’ apartment for the whole family on factory grounds. It was small and not the best quality, but it had a nice view. The factory was another story. Jurie, Suri, and Hurie making diapers! What a humiliation. They would often turn back home in tears and set out for work a second time. And when they finally got used to it, the factory owner changed, and they became slaves. The new owner said that since he was giving them a roof over their heads, he did not have to pay. When he found out that Jurie was looking for a scholarship because she wanted to study, he told her to choose: work or college. He threatened to evict them. Later, he went to yell at her father. “If you close this door, God will open hundreds of others,” her father replied, because he is a proud man. They moved out on their own.

Resistance and self-organization are actually a necessity. In the Lebanese state, where a civil war of all against all was raging until 1990, a great many things are simply unavailable.

They slept in a yard for several days, in a garage for several months. Eventually, they settled in the camp, and Jurie found work in another diaper factory. That was when she also took the leadership course. It was attended by women from various backgrounds. They learned from each other and shared experiences.

Jurie learned and shared between two shifts at the factory. She had the strength to do it because that new Jurie, who cried every day after work, was gone. The course brought out the old one, brave and committed. It was then that her activism began: she decided to help children learn.

Determination. How to build a school in a camp

The fate of a generation is hanging in the balance. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council’s 2020 estimates, 58 percent of Syrian children in Lebanon were outside the education system. Half of them had never gone to school. Because they had no documents, because there was no place for them, because it is too far away and parents do not have money for bus fare, because the family is poor and a son or daughter, instead of going to school, must earn money. The Syrian population in Lebanon is threatened by the spectre of a lost generation, which is why local and international organizations are scrambling to provide children with access to education.

Jurie, as she says, started small.

“The first school in the camp looked like a dollhouse: a small blackboard, a tiny carpet.”

In the next camp she lived in, there was more room. The problem was the aggressive shawish, i.e., the camp “mayor” – an administrator and intermediary in contacts with the Lebanese.

But she was determined.

“I know what it means to be deprived of a life opportunity. I wanted to give one to those kids.”

For a while, she wanted to run a school only on weekends, she felt that she had taken too much on herself. Immediately, however, there were parents who begged her – literally begged – that the school work on a normal schedule. They could not bear to see the children idly wandering around the camp.

The dollhouse grew into a school with thirty-seven students and four grades.

The biggest problem is still the shawish.

“He’s greedy. He thinks he should get something out of it, “Jurie says, sipping a hibiscus tea.

A few times, she discovered rubbish and even human excrement in the school tent. Someone tore her tarps, stole wood, and once even walked out with a portable toilet.

The shawish went so far as to report her to the Lebanese authorities.

Thousands of Syrians pass through the local jails and prisons, usually for not having valid documents or for unfounded terrorism allegations. And often for no apparent reason, due to the general policy of discouraging “guests” from living in the country. Under these circumstances, the interrogation was unimaginably stressful for Jurie.

She explained to the officer that they were helping the children learn, they were not teaching anything “dangerous” (meaning: religion). She showed him pictures from classes. His reaction surprised her, he seemed moved. He gave her official permission to continue all her work.

It was a relief – for a while, the shawish would be out of her hair. She keeps on going. The school is undergoing a renovation, soon they are putting up a mural. The most recent donation – because that is how the school is financed – allowed her to buy wood and to photocopy the new textbooks: one for two students, because money is tight.

“And all this has brought me here, to drink hibiscus tea with you,” she wraps up her tale philosophically as the silver thread glistens on her head.

But this is not the end of it, because Jurie is not alone.

On the family side, things are tough: Jurie is the only one in the family who has a regular job, working for a Syrian NGO. Her father is too ill, her brothers do not have the papers. “It is more difficult for men to renew their right of residence, they are more often faced with discrimination from the authorities, harassment by the police,” Jurie explains.

And so, in a family that until recently lived in a Syrian village that did not even have a doctor, she, Jurie, is now the breadwinner, the only one who leaves the home, gets an education, organizes, gets things moving. Maybe this is the biggest revolution, although one without slogans or coups, happening quietly.

The younger brother had a problem with that, he tried to turn their father against her. He disliked that Jurie was going out on her own, that she was coming back late. But he would not be able to support the family, so somehow, he got over it.

Jurie is learning to negotiate. They tell her to be home at 7 pm, she gets back at 8:30. She also tries to prepare them for a longer absence. A day may come when Jurie will leave, she tells them. That she might be living in a dorm. “You have to be ready for no more Jurie,” she repeats.

“There is nothing good about the war,” Jurie’s mentor, Ola Al-Jundi, once told The Guardian. “We have been forced to change. We didn’t choose it. But now, we are not going to go back to our previous position.” Except this is not a neat success story, we are not applying for a grant. I have already turned off the recorder when Jurie starts talking about violence and harassment, the plague and fear of many Syrian women. She talks about officials promising a scholarship for naked photos, about fake job offers, blackmailers. Off-the-record stories which make my hair stand on end.

We are scheduled to visit the school in the morning, but that night Jurie texts that her mother is feeling worse. She has a heart condition, but they sent her from the hospital back to the camp. “We are prepared to even go to Syria to save her,” Jurie writes. Who knows what awaits them there? But the health care back there is free.

Solidarity. Syrian organizations together in action

There is nothing to romanticise about resistance. As the Palestinian-American anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod wrote about resistance years ago in the influential text The Romance of Resistance, its strength is proportional to the intensity of everyday oppression. The narrative of “life knocked her down, and she got up anyway” obscures another, the one of structural violence. But neither must resistance be overlooked, because that leaves only victims and pity.

The narrative of “life knocked her down, and she got up anyway” obscures another, the one of structural violence. But neither must resistance be overlooked, because that leaves only victims and pity.

It is early December and the days in Bekaa are still quite warm, but in winter the weather can be cruel. Three years ago, snowstorms and floods swept through the valley. The camps experienced a real cataclysm, people lost everything they still had, 600 people were left homeless.

“All Syrian organizations, large and small, got together,” says Inga Hajdarowicz in the taxi taking us to the next meeting. “It was amazing. The schools and centres they had been running were converted into temporary shelters, employees ferried people there from the camps. Women coaches worked the communal kitchen. The only doctor on the scene was a Syrian refugee, Dr. Feras Alghadban, who toured the camps in his mobile clinic van. All Syrian men and women whose tents were not flooded helped, crowds of volunteers. Then I understood: these people have the know-how and the ability to organize, which many of them learned during the revolution. If not for the need for money and other resources, international organizations would not be needed here. The latter did not arrive until two weeks later.”

Action. Against child marriage

Actions from the inside are also more effective. This was the case with the public campaign against child marriage. In the Syrian community in Lebanon, this problem is on the rise. The numbers are much higher than in Syria itself. This is largely due to the economic collapse: marrying off a daughter is the easiest way to relieve the household budget.

Women Now had the idea that, instead of planning top-down actions, it is better to enable the people who have first-hand experience of the problem. The experts – the women themselves.

Inga shows me photos from the campaign debrief event on her phone. The room is packed to bursting. On the stage, a clergyman in a white turban, a woman doctor, another – a psychologist. Then, on the same stage, fathers who have signed a pledge that they will not marry off a child before the age of eighteen. In total, there were 167 of them.

To make this happen, teams of Syrian women worked for several months in various villages in Bekaa as volunteers. First, they trained each other, then they prepared an action strategy. They visited people in camps, told their own stories, presented biological and psychological arguments against early marriage. They showed a video in which clergymen of different faiths explained that it was contrary to religious precepts. They argued that it was better to invest in the education of children and their future position on the labour market. They returned for feedback, improved their strategy.

Their conclusion was that it was best to focus on the fathers. So they made them ambassadors for the project who would talk to other men. The women set themselves the goal of breaking off fifty-five betrothals. It worked for more than sixty.

“When we visited families, we didn’t bring a recorder, we took no notes,” Fatima says. “We didn’t want to create a distance like the employees of large organizations do.”

The latter plainly are not held in high esteem here. Unlike Fatima, one of the main campaign coordinators.

Courage. How to fight for yourself and other women

In Syria, Fatima had a three-story house and orchards of apple trees, to which, before leaving, she said, “Goodbye, my children.” Now her whole life fits in a little room where we just sat on the floor amidst pillows.

By the front door hangs a poster with the red logo of a campaign combating violence against women. There is a gas cylinder in the room, which Fatima uses to make us coffee. “I have a studio apartment, like the Europeans,” she says sardonically, as she puts the cups on a small table. When we are done talking, it will be covered in used tissues. Ours.

“I got married when I was sixteen,” Fatima says. “Because I wanted to. My mother was against it, she didn’t even say goodbye to me when I moved out. My father had no opinion, although the decision was his to make. My idea of marriage – a white dress, a knight in shining armour, a fairy tale. I had no clue.”

He had graduated from the police academy. His work involved a lot of travel, he was rarely home. Things were tolerable. But then came the revolution, which coincided with his retirement. They were home together for many months. The violence and harassment she had always experienced from him intensified a lot. Even more so because she supported the revolution, and he – the regime.

“His former colleague called him once,” Fatima says. “He said I was seen at a demonstration, that I was the only woman to have my face exposed. He told him to ‘do something about’ me.” So he did – so much so that she can not forget it to this day.

But there was no other way she could have acted. All the people who took to the streets in 2011 had their reasons, and so did she. She saw her brothers and sisters: they had gotten their degrees, but they were not doing well. There was corruption and sectarianism everywhere. But that was not the worst. Twenty years earlier, one of the brothers got into a fight, they arrested him. And then they gave them his body, said he had had a heart attack. The truth was never found out.

“So each of us was on the street with their own pain,” Fatima says. “Mine was even greater because I had a regime man at home. I had personally experienced all kinds of torture and harassment.”

She ran her own company, a small printing firm where she printed leaflets and banners for protests. Together with other women from the area, she prepared meals for the demonstrators, cared for the wounded, made headbands with the flag of a free Syria. She went to demonstrations. Young men surrounded them in a circle to make them feel safe. “Most of them are dead today,” Fatima says in a low voice.

She knew she was risking her life too, and it was not about Assad, or at least not just about him. But she did all this behind her husband’s back.

“Weren’t you afraid? Why didn’t you cover your face at the protests?” I ask.

“That was the whole point,” she replies after a moment, raising her head.

After arriving in Lebanon, she also became politically involved, although, as she says, she was always punished for it.

“I had lost a lot of family members in Syria. When he beat me, I thought my life was no more precious than theirs. I did not care if I survive,” she explains.

Maybe she never would have decided to get a divorce. In her family, it was a big taboo, a disgrace to a woman. Besides, the kids. If she left her husband, she would lose custody of them.

But he decided to marry off one of their daughters at the age of fourteen. Soon after, she returned to them with her baby, because her husband was also abusing her. She was deeply depressed, smashing glass objects and cutting herself with the shards. He still sent her back to her husband.

About that time, Fatima’s friend told her about the leadership course. “It’s about raising political awareness, are you interested?” the friend asked. She was, very much so. After all, she had been involved in the revolution, but she did not know the theory – democracy, the state, the law.

Besides, it was not just about politics. She met women there who, she says, are her “support system” today. She got stronger and she learned what to do, step by step: doctor, examination, lawyer. She got divorced and then helped her daughter do the same. She saved her, she saved herself.

“This course was a turning point in my life,” she concludes.

And now there is the campaign. She would like to start working with young men, but as a team they decide democratically and horizontally, so she must first present the idea to the rest of the group. She herself supervises several working groups, meets with the coordinators, her phone does not stop ringing.

But there is more to it than joint action. They go on trips together, take care of each other when sick. “I lost my family in Syria, but I’m building a new one here,” Fatima says.

Support. Recovering mental health

“Healing with purpose” is a term used by Yasmine Shurbaji, a psychologist merely in her thirties who has been working at Women Now for seven years. “These women don’t stop, they treat recovery not as an end in itself, but as a tool,” she explains.

In Syria, Yasmine studied dentistry. She only switched to psychology in Lebanon. “My community needed support,” she says.

It is Saturday afternoon. Yasmine’s apartment is pleasantly cluttered. The short-haired mother once again asks if we definitely do not want to eat, loud music and a child’s laughter reaching us from the kitchen.

Yasmine closes the living room door and starts talking. Her words pour out before I have the time to ask anything. The subject is oceanic. And bitter, like the laughter of Mahasen, one of the leadership course graduates, who, when asked how her children are doing, will answer: “We all need help.”

Yasmine tells us that in her work she usually deals with post-traumatic stress disorder or the problem of violence. That the rates of the latter increased alarmingly during the pandemic, which coincided with the economic collapse in Lebanon. That sometimes violence is a ghost from the past, a relationship with a violent husband, former or present, and sometimes it is very fresh. Unmarried or widowed Syrian women in Lebanon are exposed to it in various areas of life: the labour market, housing.

“Women say: so what if I feel empowered and strong if I cannot afford to feed my children, or I can’t leave my husband because I have no income?” explains Yasmine.

That is why Women Now recently launched the Cash for Protection program. It was created for situations where money is the bulwark against violence. This is yet another example of the comprehensive approach to empowering women. Not just the home, not just politics, not just economics – it is about taking care of everything at the same time.

“Gender-based violence, gender as such, women’s rights – these are topics that take time,” says Yasmine. “We see many positive changes in Lebanon. Women are becoming more aware of their rights, and they are learning from Lebanese women, whose fight is farther along. At first, they are often shocked to learn, for example, that husbands have no right to force them to have sex.”

For this reason, Women Now applies the principle of baby steps, gentle change. If they are to have a revolution, then it will be one that does not devour its daughters, but rather embraces them.

Women are becoming more aware of their rights, and they are learning from Lebanese women, whose fight is farther along. At first, they are often shocked to learn, for example, that husbands have no right to force them to have sex.

“We are all daughters of the same society, as we tell the participants. We don’t have to bring archaic beliefs and traditions with us here, we all know how much they have hurt us,” says Yasmine, who calls herself a modern but devout Muslim.

We listen to her, nibbling on soft, colourful iced cookies from Daraya, her hometown. I do not ask how to buy them in the Bekaa Valley, but I am not surprised – the stream of trucks and vans flows every day down the highway to Damascus and back.

Located on the southern outskirts of the Syrian capital, Daraya is a special place. Writing about it, the Lebanese researcher Joey Ayoub titled his text An idea called Daraya. It was a hotbed of civic activity before the revolution, among others thanks to Abdul Akram al-Saqqa, an imam and thinker who led a pacifist movement.

In 2011, Daraya became one of the fiercest points of resistance against Assad, and practically Yasmine’s entire family took part in the revolution.

Yasmine was a member of the Free Women of Daraya coalition, which was formed by independent groups of women and girls. They used Skype to have classes on the constitution, family law, citizenship. Together with the Free Men, they organized demonstrations, and when the city was besieged, they ran a communal kitchen.

“In Daraya, we had a real system, a great organization,” Ola told me proudly two days earlier. As a student, she had been the only woman on the local coordination committee. “The place has always had a different, more open way of thinking.”

So before coming back to the topic of psychology, Yasmine makes a statement.

“What I do at Women Now is more than work,” she says. “It is a revolution, which have the opportunity to complete.”

These words resonate forcefully in a room where pictures on walls are adorned with knitted flags of free Syria. The largest of them shows a greying man in a leather jacket. He sits in a cafe or restaurant, looking somewhere to the side. From the photo on the opposite wall, a young man of 20, with a gentle look and a smile, looks at him.

“This is Inas and baba (dad),” Yasmine says.

Baba disappeared in 2011. He was arrested in the street during Ramadan. Inas got picked up from the university. They were gone without a trace. Not until 2018 did they receive their father’s death certificate, although “certificate” is too much said: it was a handwritten piece of paper without any stamp. It said that baba died in Saydnaya prison (the most notorious one) in 2013. They still have no news of Inas.

“My experiences are the same as those of the women I work with,” Yasmine says. “Their stories take a toll on me, so I have to be under constant supervision.”

She proudly reports that the number of women interested in mental health classes has long exceeded the numbers for English or computer science, although the opposite was the case at the beginning. On the one hand, this is good, because a taboo has fallen. But it also reflects the sea of suffering that the Syrian community is drifting through.

“And yet, as soon as people manage to get back on their feet, they start doing things. They create their own projects, get involved. That’s what I think is special about Women Now. Recovery is a road to something more,” says Yasmine.

To see the community’s pain in your own suffering and turn it into the strength to act – this strategy is exemplified in Yasmine herself, who coordinates the work of the Lebanese branch of Families for Freedom.

To see the community’s pain in your own suffering and turn it into strength to act – this strategy is exemplified in Yasmine herself, who coordinates the work of the Lebanese branch of Families for Freedom.

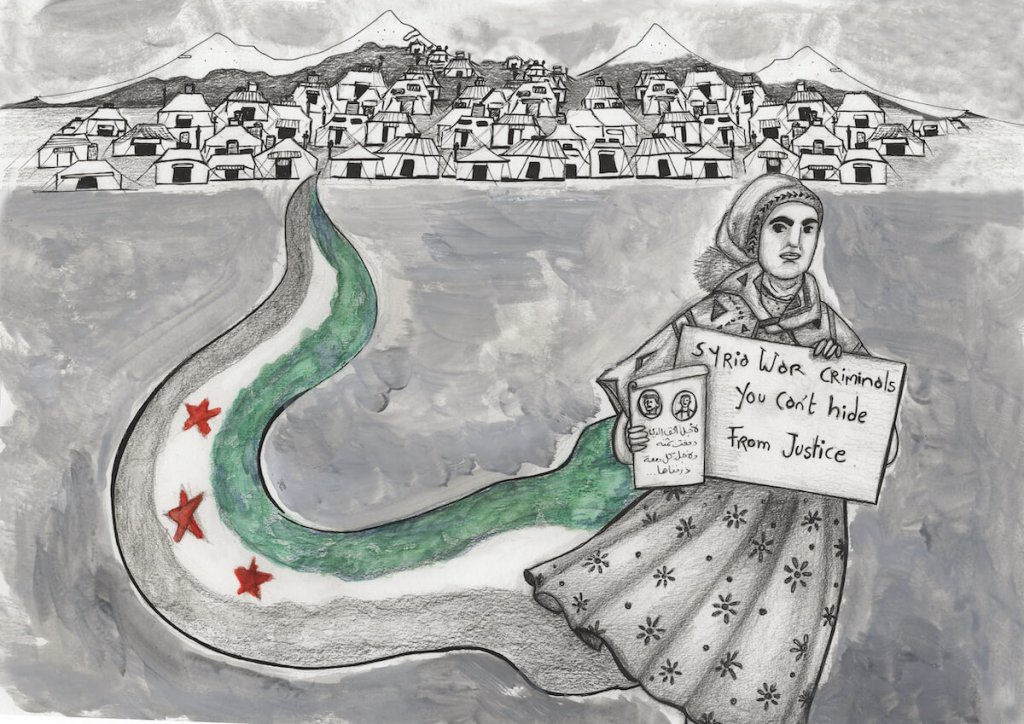

It is a movement of Syrian (mostly) women, modelled on the Argentine Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. They are wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters demanding the truth about relatives who went missing during the war. They publicize, they lobby, they demand justice. They cry out that the supposed reconstruction of Syria is taking place over the bodies of their families. They can be seen in various cities in the Middle East and Europe, standing in public with portraits of their loved ones.

“We take our strength and motivation from the people who rule Syria,” Yasmine says. “They desire power and money. We have an equally strong love for our rights.”

Strength. To start living again

“Barazilia” – shines the red neon light of the gas station as we leave Yasmine’s. Many businesses here have such names: stations, shops. It is a trace of Lebanon’s migratory past, as the Lebanese, fleeing violence and poverty, often found a safe haven in Latin America, including Brazil.

Constant human flux is nothing new here, and neither is it anywhere else in the world. Each of the past migrations escapes, journeys shifted the established structures and relationships. The cast of roles and the balance of power were changing, family microcosms swirled. Hundreds of parallel micro-revolutions and simultaneous retaliations transpired as life was changing, knocked off its normal course (like in Europe after the war, like after all wars).

But such changes never happen without pain, and this fact also needs to be told.

Mahasen is an expert on the subject. The petite woman, wearing one earring, her lightly greyed hair tied in a simple ponytail, is wearing a velvet tracksuit. She is spontaneous and cordial, children must love her. Tired after a long road that led through several cities in Syria, she ended up here in the Bekaa Valley for now.

“I was surprised by my own strength,” she says in a hoarse voice, as we sit down on the soft carpet in her living room. “After my husband was arrested, I didn’t eat for three months. I felt like I couldn’t go on without him. I couldn’t even catch a bus on my own, I was so panicked about living alone. I didn’t think I’d be able to replace a gas cylinder. Turns out, I can do that and a million other things.”

A playful smile crosses her face. “A woman doesn’t need a man to live, he’s just an added value in bed.”

She snapped out of it, she says, because she realised that the children needed her. For them, she had to act strong, even though she felt anything but. She read them fairy tales as shells fell all around. She smiled, even though she was terrified. During the massacre, she calmly opened the door to the soldier who came to shoot them, but when he saw how many people were hiding in the house and that there were old people and children there, he slapped his hand to his forehead and left (Mahasen still asks herself why he let them live).

She, a mother of seven, who had never worked before, got a job at a sock factory to support them. When they got to Lebanon, she took every job possible. She wipes her nose. Emotions get to her when she remembers that time, you see. She talks about odd jobs, driving from place to place, washing windows. “In Syria, I hadn’t realized the value of education,” she says. “But in Lebanon, it was like the Last Judgment: all that mattered was what you brought with you. If you had no skills, no education, no diploma, you were in for a rough time.”

In the meantime, she took a quick practical course on women’s rights (or rather the lack thereof). When she had wanted to leave Syria with her children, she first had to get permission from their missing father’s brother, her brother-in-law.

“Imagine this: you raise them, you are with them every step of the way, and then, at such a time, you have to beg for the permission of a man you barely know,” she bristles.

She later learned about all this in the leadership course.

“These are very important things that I didn’t know before,” she says. She took the course because she had finally found a safe haven and a job as a kindergarten teacher in Gharsah, the school founded by Ola Al-Jundi. All the staff took it. With “superhuman” effort, she says, she managed to put all the children in schools and rent a decent apartment. She had done it.

And then he came back.

He had been imprisoned for eight years for political reasons. Or rather, he still is, because according to Mahasen, his soul remained there.

“When he found out I was working, he stopped talking to me,” she says. “He says I’m scary, that I’m strong and terrible,” she adds with snark. “Maybe if he hadn’t been detained, he’d be more open. But his social clock has stopped.”

Her father and brothers, equally conservative, accepted the changes. Her father supported her and her sisters in their search for work and courses. Her husband does not like her leaving the house, does not understand that his daughters are now women, can not use a smartphone.

“I’m not angry with him, I feel sorry for him,” Mahasen says sadly.

At first, the daughters ignored him, did not consult with him – as if they forgot that he had returned at all. Frankly, so did she, on occasion. Their daughters dress more freely now, go on school trips with boys, stay out late. These are things that would be impossible in Syria. “In past Syria,” Mahasen corrects herself.

Some changes did come with the revolution. In the air raid shelters, male and female bodies huddled together. Men got used to women being the ones to leave the house, because they were less likely to be frisked. The men themselves, Mahasen says, were out of the equation for a while. She thinks the same is true in Lebanon: women are more likely to find work because they are less picky. Men are more often fixated on going abroad, they want to earn more.

Now, her husband and her children are in open conflict. She tries to defend him, reminds them of what he has been through. “He wakes up at night from nightmares, thinks about his cellmates whom he left behind,” she says. “He wants to find a job, but he doesn’t have one. What he has are health problems: he’s suffered a heart attack and he has nerve damage in one leg from torture.”

Two hours into our conversation, Mahasen confesses that their youngest son has run away from home because of a row with his father. Not for the first time, but he has been gone for two months. Fortunately, she knows who he is staying with, but she is still very worried.

“When you start breaking down barriers, you have to be ready to lose people around you,” she says.

“And who did you gain?” asks Inga.

“To be honest,” Mahasen replies, “mainly, I gained myself.”

There are other stories. Ones we heard in passing, second-hand, or not meant for print. About blackmailers who threaten to “smash your head against a wall if you don’t…” and police that ignores you if you are a Syrian refugee. About Lebanese soldiers who stuff you into a van and say that in half an hour you will be deported to Syria, and after 30 minutes they open the door and say: “just kidding”, about dating sites controlled by blackmailers from Hezbollah. About folic acid deficiency, making children in the camps be born smaller and smaller, and about the shortage of medicines in general. These snippets spin like a dark kaleidoscope and leave a more suffocating residue than fumes and smog in Bekaa.

Justice. The sense of grass-roots action

As I finish writing this, it is still winter. The Bekaa Valley is being hit by the biggest snowstorms in decades. In Jurie’s newly renovated school, a wooden ceiling has collapsed under the weight of snow. “The situation is crying here,” says the machine translation of her Facebook post. Translations do not require a broken heart emoji.

Together for Justice had to suspend activities for a while because it had not received a new grant. I wonder if Ragda can afford the mazut.

Fatima has applied for a humanitarian visa and wants to leave for Europe as soon as possible. She is terrified, her ex-husband sends her threats through acquaintances. It is serious, because he has joined Hezbollah and works with the Syrian embassy.

Ola from Daraya temporarily suspended her activism because after last year’s election in Syria, which was won by Assad, she needs time to think about everything she has lost.

Most of the women we spoke with want to leave Lebanon. Mostly, to finally stop being afraid: of Assad, of tomorrow.

“The weight is sometimes unbearable,” Yasmine’s words echo in my head.

But there is also this.

On January 13, a German court sentenced Anwar Raslan, a Syrian intelligence colonel, to life in prison. He is the first war criminal in Syria to pay for his deeds. Admittedly, he was more of a cog in the machine than the brain, but the verdict is historical, because it gives hope for more. It also proves that grass-roots action makes sense: it would not have happened if not for the testimony of hundreds of witnesses, thousands of documents and photos smuggled from Syria, the pressure from activists.

Looking through the pictures from Koblenz, where the trial is held, I see Yasmine. She stands, proud and brave, in front of the courthouse with the other members of the Families for Freedom. In one hand, she holds a picture of her father and Inas. In the other, a banner that says: “Syrian war criminals, you will not escape justice.”

I want to thank Inga Hajdarowicz for the cooperation and invaluable support, without whose knowledge, contacts, and commitment this text would not have been possible. I am thankful also to our excellent interpreter, Wissam Tayar.

If you wish to support the school run by Jurie in the refugee camp, click here: patronite.pl/szkolajurie

This text was created with the support from the Henryk Wujec Civic Fund.

This reportage was published in the August issue of the monthly magazine “Pismo. Magazyn Opinii” (8/2022) under the title Rewolucja przytula swoje córki.